It's easy to feel hopeless. We're knee-deep in a backslide into fascism and lawlessness, and structural change seems all but impossible. But in historical moments like this, as they say, you can't know your future if you don't know your past - and a bit of inspiration from forces of change certainly wouldn't hurt.

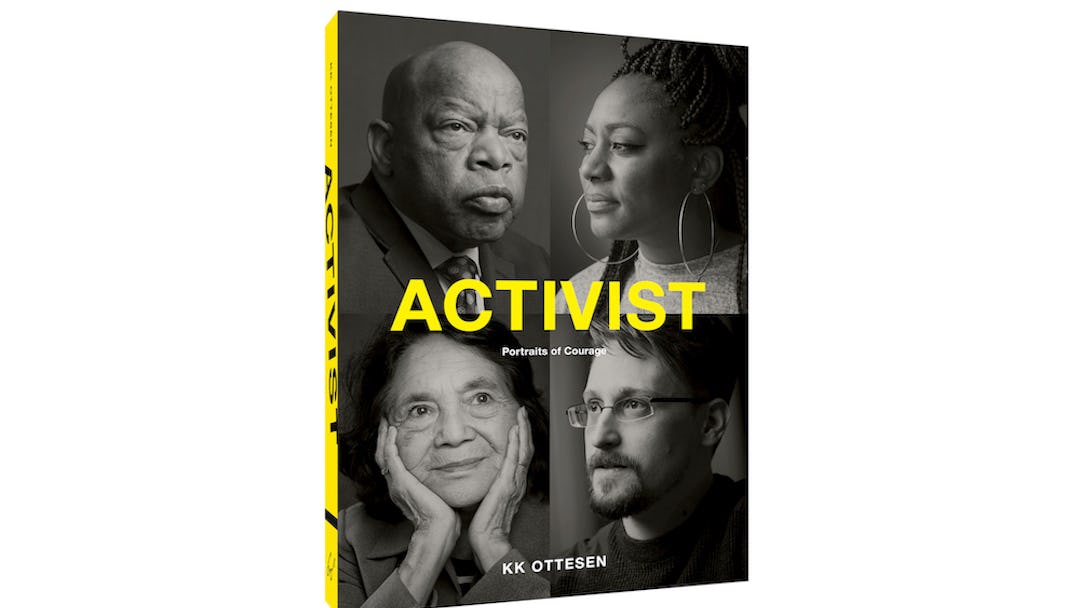

Into that void steps the new book Activist: Portraits of Courage, in which author KK Ottesen seeks out the knowledge of 40 iconic American activists, including Alicia Garza, Bill McKibben, Cecile Richards, Gabrielle Giffords, Marian Wright Edelman, Phyllis Lyon, Angela Davis, Shepard Fairey, and Edward Snowden. Illustrated with remarkable new photographs, and full of pearls of wisdom and advice, Activist is a work of much-needed guidance and hope.

We're pleased to present this excerpt, featuring an interview with Tarana Burke.

FROM "ACTIVIST: PORTRAITS OF COURAGE":

Civil rights activist Tarana Burke founded what would become the #MeToo movement in 2006 to support survivors of sexual violence, particularly young women of color from low-wealth communities. Burke was named "Time" Person of the Year 2017, with a group of activists dubbed “the silence breakers.”

I come from a really conscious family. My mother had been part of the Black Power movement in the ’70s, so I was raised with a lot of consciousness. I knew my history, and I knew the things around me that were unjust. But I didn’t have an entry point to do something about it. Then I joined an organization when I was fourteen called the 21st Century Youth Leadership Movement. The crux of 21st Century was letting young people know, you’re a leader—now. There’s no waiting period. It was a huge mind shift for me. Like, I don’t have to just read about this and be angry about it and debate it in class and stuff. We can go and do something. We can go organize the marches and rallies. We can do that stuff ourselves. And so we did. I never thought about being fourteen or fifteen. It just literally never occurred to me. Nothing about the organization, nothing about how we were trained, focused on our age. The model was essentially: Do the work. Learn by doing.

This is ’88, ’89, and New York is exploding with racial issues. It’s just one thing after another after another. Yusef Hawkins was killed. The Central Park jogger case was the next year. We had just come back from a nine-day camp, and a girl in our program had been dating Yusef Salaam, one of the guys who was accused. She was just, “That’s not Yusef, they didn’t rape anybody.” We were upset about their portrayal in the media—and not just about them, but also, like, it could be any one of us. And I remember saying, We should have a press conference to tell these people that there are positive black youth, and they cannot criminalize black youth. And I remember standing outside, and we made our speeches. We were high-fiving afterwards. It was a big deal for us, it was so powerful, like, Oh, our voices matter.

For a lot of people, it feels like we went from the civil rights movement to Trayvon Martin. Right? The work that we did in the ’80s and ’90s is not well-documented. They don’t really understand that there were those of us fighting against police brutality for decades. You know, Abner Louima, Amadou Diallo, Eleanor Bumpurs—I mean, there’s case after case after case that we were in the streets about.

There’s no way that I could have been prepared for this #MeToo moment had I not had grounding in this work. No way. Part of the reason why the media shifted away from Alyssa [Milano] early on is because she could talk about her feelings, and her experience, or build on the momentum around Harvey Weinstein, but thinking about a movement, that’s not her work. People were hungry to understand why this was happening. So, it gave me an opportunity to come in and say, Listen, what this hashtag has done is allow you to see the breadth and depth of this issue. And now we need to dig into the issue.

We have never confronted sexual violence in this way in this country. We’ve never taken a step back to listen, to really understand the effects of sexual violence, from sexual harassment to rape and murder. We’ve missed opportunities, from Recy Taylor to Anita Hill. And so, you’re dealing with millions of women, mostly, who have been shamed into silence forever. That’s not even an exaggeration. And people are pouring their hearts out, having their own personal reckonings. Like, “Oh my God. I have an opportunity to say this out loud, and people will hear me, and I want to get this off of me.” It’s been wonderful to see all these people coming forward and talking about their experiences and sharing this hashtag on social media to say: “You’re not alone.” Particularly people who said it for the first time. You put it out in the world. It came out your lips. You’re still alive. You made it. It’s out there, and you lived.

But I think the media’s done a terrible job of getting into the issue. It’s fed the fire. In those initial articles, women were not calling for anybody’s head. They didn’t say, as a result of this, we want Harvey Weinstein out. We want him dead. The call was, “We want the world to hear what we’ve been through. We want the world to understand the system that we are living in that allowed this [to] happen. We want the world to see what it takes for a woman to survive and thrive in this country.” But we skipped over that. And it became: These women spoke, Harvey Weinstein lost his job. These women spoke, Matt Lauer lost his job. These men spoke, Kevin Spacey lost his job. It became this sicko tennis match, almost. Like, “Ooh, let’s see what’s going to happen next.” The problem is, culture shift doesn’t happen in the accusation, it doesn’t happen in the disclosure. Culture shift happens in the public grappling with these questions. So, we have to have, and be, comfortable with, a public grappling. Because nobody has firm, definitive, perfect answers.

When I meet survivors, there’s a part of me that knows. I know by how they approach me; I can feel it. I have been this way before #MeToo went viral. I’ve been in places like Red Lobster—true story—and I went out on a limb, big time. It was a white family in Alabama sitting at the table across from me, and everything in my body knew that that little girl at that table—she might have been about eight—that something had happened to her. The mother went to the bathroom, I just went up and I said, “Your daughter’s so beautiful.” And she’s like, “Oh, thank you.” I said, “I do work with kids and some of the kids I’ve worked with have experienced trauma.” I was being as vague as possible. “And this is going to sound really strange, but if you would talk to your daughter and make sure she’s okay.” I said, “I try to tell all parents that.” She said, “It’s so crazy that you said that. Our family is dealing with an issue . . .” The girl had been touched by a family friend. And me and that mother stood together in the Red Lobster bathroom crying.

This movement is about empathy. I just try to carry the message I wanted when I was a kid: It’s not your fault, it’s not your shame to carry, it’s not your blame. And you’re not out here by yourself; nothing’s wrong with you. There’s no special curse on you that made this happen.

I spoke in Philly the other night and a girl said, “How did you find your voice?” I said, Listen, sweetheart. Your voice will find you. Follow your heart. Your voice will catch up. If you’re passionate about the environment, or racial justice, or whatever it is, try everything. The best advice I got when I was young was that I was powerful. Now. That there was nothing I had to do, or change, or become, to be powerful. Young people feel so limited. It feels out of reach to them, which is unfortunate. They don’t know where to start. Every day I get an email, like, “I want to start a movement, and I’m just trying to figure out how I can get my hashtag to go viral.” And I’m like, Please stop. Just do the work. There are no shortcuts. If #MeToo didn’t go viral last October, I would still be marching around with my little “me too” T-shirt on and trying to get people to talk about it, trying to make a difference.

Excerpted from "Activist: Portraits of Courage by KK Ottesen," out now from Chronicle Books. Used by permission.