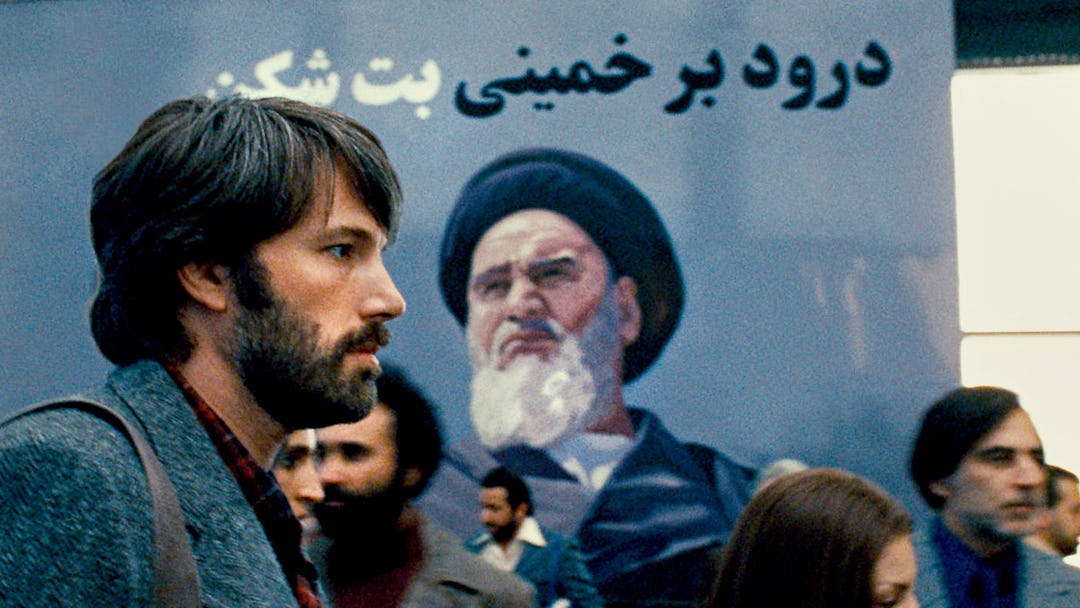

Argo, Ben Affleck’s true story of American hostage extraction by way of Hollywood fakery, hits DVD and Blu-ray today on its way to a possible Best Picture prize at Sunday night’s Oscars. But as with its fellow nominees Zero Dark Thirty and Lincoln, Argo has been the object of some concern over historical accuracy, culminating in yesterday’s proclamation by Salon’s Andrew O’Hehir that “Argo doesn’t deserve the Oscar” because it “uses its basis in history and its mode of detailed realism to create something that is entirely mythological.” While Affleck’s film is certainly not our favorite of the Best Picture nominees, we’d have a hard time arguing that a film’s fast/loose play with the facts should be a disqualifying factor. In fact, plenty of pictures we’ve been rather fond of weren’t exactly slavish to historical accuracy; we’ll take a look at Argo and its “true-ish story” brethren after the jump.

Argo

We’ve been singing the praises of Argo since its release in October, but make no mistake: there’s a whole lot of fiction in this true story. Those who were intrigued enough by Ben Affleck’s thriller to track down the Wired story that inspired it may have been disappointed to learn that some of the scenes that seemed too good to be true — specifically those at the film’s white-knuckle conclusion, with the tense airport interrogation and the runway pursuit — were, in fact, not true. Disappointing? Sure, especially considering how painstakingly other elements of the story are replicated. But Affleck and screenwriter Chris Terrio appear to have followed Mark Twain’s advice: “Get your facts first, and then you can distort them as much as you please.”

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre

Tobe Hooper’s 1974 cult classic opens with a matter-of-fact crawl (read by a young and unbilled John Larroquette) warning viewers that the film “is an account of the tragedy that befell a group of five youths, in particular Sally Hardesty and her invalid brother, Franklin” one “idyllic summer afternoon.” The film’s marketing campaign seized on the film’s true story roots, which were made even more explicit when its remake was released in 2003. But according to Snopes, Hooper’s film was less based on a true story than on his own trip to the hardware section of a Montgomery Ward’s, where a display of chainsaws got his cinematic wheels turning. But there was no such person as Sally or Franklin Hardesty outside of Hooper’s screenplay; the “true story” angle came from Hooper being secondarily inspired by the story of Wisconsin serial killer, cannibal, and necrophiliac Ed Gein. But that’s nothing new — Gein also loosely inspired Psycho and The Silence of the Lambs, among other horror classics. More importantly, it doesn’t really matter to the film. While the opening crawl, coupled with the film’s grubby, low-budget aesthetic, lends it something of a documentary realism, the knowledge that Leatherface was a fictional creation doesn’t keep Texas Chain Saw Massacre from being serious nightmare fuel.

Shakespeare in Love

John Madden’s surprise 1998 Best Picture winner tells the tale of how William Shakespeare (Joseph Finnes) came to write Romeo and Juliet while falling madly in love with Viola De Lesseps (Gwyneth Paltrow), a beautiful actress masquerading as a male actor in his company. But Viola was manufactured from whole cloth (as was her betrothed, the Earl of Wessex) by screenwriters Marc Norman and Tom Stoppard, who named her after the heroine of Shakespeare’s later cross-dressing comedy Twelfth Night, indicating that she also inspired that work. In fact, most scholars agree that Romeo came less from Shakespeare’s personal romance than from earlier works by Arthur Brooke and William Painter. But Shakespeare in Love is upfront about its fanciful nature; it’s full of inside jokes and sideways winks, indicating that it’s not exactly a scholarly work.

Good Morning, Vietnam

Robin Williams landed his first Oscar nomination — and turned his floundering film career around — with Barry Levinson’s 1988 Vietnam comedy/drama, in which he played Adrian Cronauer, a real-life disc jokey for the Armed Forces Radio Network who entertained troops “from the Delta to the DMZ” with his off-playlist rock and soul selections and outrageous comic monologues. But the character was more Robin Williams than Adrian Cronauer. As noted by Cracked, not only were the character’s off-air adventures entirely fictional, but “he rarely resorted to flat-out comedy bits” on the air. He left his post not because he got mixed up with Vietnamese nationals, but because his tour ended. And contrary to the anti-authoritarian, anti-war liberal Williams played, Cronaeur was a “lifelong card-carrying Republican” who worked for George W. Bush’s 2004 re-election. So, yeah, the real Adrian Cronaeur story would’ve been a lot less exciting — and had a much sadder ending.

Frost/Nixon

Ron Howard’s riveting film version of Peter Morgan’s surprisingly gripping play finds its emotional climax in a late-night phone call from Richard Nixon to David Frost, in which the drunken former president finally opens up to the British journalist and lets him see how he can get Nixon to come clean on camera. Only trouble is, the scene never happened. According to biographer Jonathan Aitken, the late-night call was, “from start to finish, an artistic invention by the scriptwriter Peter Morgan.” But director Howard defended it on the usual grounds of artistic and dramatic license — and he’s right. Shifts in relationships and power dynamics seldom happen as cleanly and efficiently as this, so sometimes an incident must be contrived in order to move the story forward in a timely manner. As a result, Frost/Nixon makes for great drama, if not great documentary.

Lean on Me

This 1989 drama was one of the first leading roles for Morgan Freeman, and the character of New Jersey school principal Joe Louis Clark gave him the opportunity to show what he could do in a central role: wielding a bullhorn and a baseball bat, Freeman is a monster, fierce and furious. Clark’s is a classic underdog tale, of the unorthodox administrator who comes into a bottom-rung school and cleans up his act, raising test scores and inspiring his students. The real story was a little more complicated. According to The Washington Post, the test scores went up in no small part because Clark had tossed out so much of his student body — and even then, “they remained quite low when compared to other New Jersey schools. The school’s college acceptance rates barely changed. It took a particularly egregious talent show strip-tease incident to begin to defeat the persona he constructed. Yet by and large, his myth persists.” Strip-tease incident? Um, we’ll take the inspiring “school song” resolution of the movie, thank you very much.

Rudy

This 1993 college football drama is one of the most beloved of all sport flicks, voted the fourth-best of all time by ESPN.com’s “Sports Nation users,” who presumably would know. Its most famous scene (one quoted and partially recreated just last year on The Newsroom) is the so-called “jersey scene,” in which plucky Rudy’s teammates lay their jerseys on the desk of villainous Coach Devine as a show of protest, so that their bench-warming teammate can finally get some field time. Well, we realize this is the sports movie equivalent of revealing Santa Claus isn’t real, but neither is the jersey scene. In fact, Devine not only decided himself to put Rudy into that last game, but agreed to let the movie cast him as the bad guy. In his autobiography Simply Devine, the coach writes he told screenwriter Angelo Pizzo “that I would do anything to help Rudy, including playing the heavy. I didn’t realize I would be such a heavy.” The movie might’ve painted Coach Devine as a bad guy, but Pizzo knew what he was doing: the conflict with the coach and the tearjerking “jersey scene” necessitated by it are why Rudy is still such a favorite.

Amadeus

Peter Schaffer adapted his play for Milos Forman in 1984, to critical huzzahs and an astonishing eight Academy Awards (including Best Picture). He tells the story of Antionio Salieri (F. Murray Abraham), the mediocre composer and contemporary of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (Tom Hulse), who is driven mad — and perhaps to murder — by his intense jealousy for the genius, who is portrayed as a giggling, promiscuous vulgarian. However, as The Guardian pointed out, the film is rife with inaccuracies, from its portrayal of Salieri — who had eight children by his wife and may have had a mistress as well — as “a sexually frustrated, dried up old bachelor” to its incorrect assertion that Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro and Don Giovanni were flops when initially performed. But most importantly, the rivalry at the center of Schaffer’s play and Forman’s film seems entirely fictional: “Mozart was on good terms with Salieri at the time of his death,” according to The Guardian, “inviting him to The Magic Flute and writing warmly of him in his diary. Later, Salieri gave his bereaved younger son free music lessons.” Gotta say — that doesn’t quite pack an Oscar-worthy wallop. We’ll take the fierce-rivalry-and-possible-poisoning angle, if that’s cool.