Hollywood, this is why you can’t have nice things. A couple of weeks back, word broke that Quentin Tarantino had finished a new screenplay called The Hateful Eight, described as a Western with plum roles for recent Best Actor nominee (and Django Unchained bit player) Bruce Dern and Tarantino fave Christoph Waltz, and there was much rejoicing. That celebration ended earlier this week, when Tarantino discovered that the script had been leaked — apparently by someone connected with either Dern, Michael Madsen, or Tim Roth (anyone who’s seen Reservoir Dogs knows you can’t trust Roth) — and pulled the plug on the entire project, leaving various sites to see who could collect pageviews by distributing a stolen screenplay first. (Surprise — Gawker won!) But Tarantino’s unproduced script is in good company; here are a few other famous abandoned screenplays we’d love to have seen.

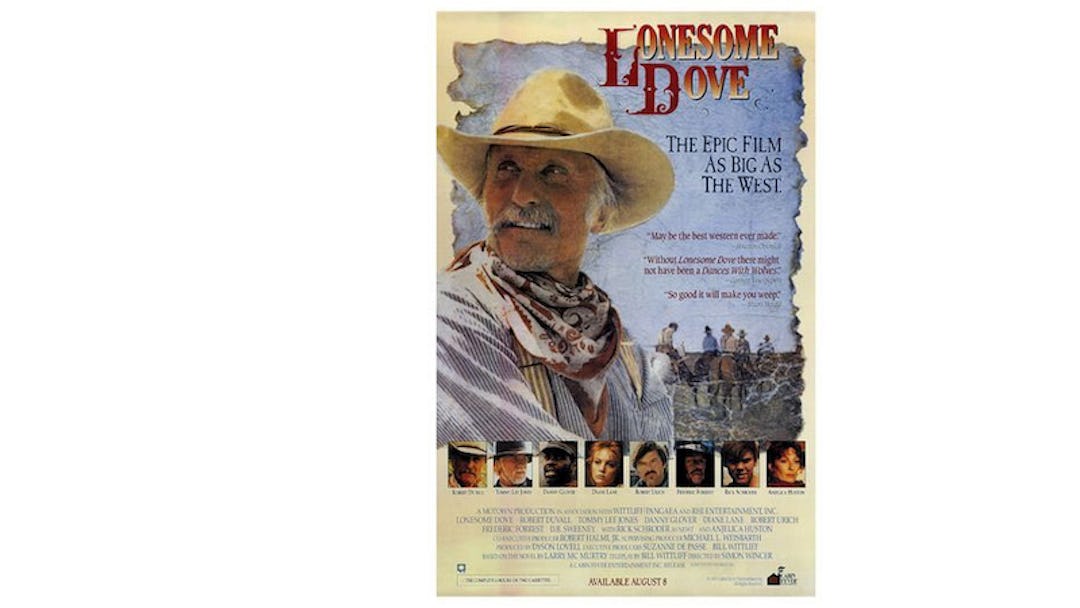

The Streets of Laredo, by Larry McMurtry and Peter Bogdanovich

While helming the documentary Directed by John Ford, Bogdanovich got the idea of teaming up John Wayne, Henry Fonda, and James Stewart to create an all-star send-off to the Western, and he collaborated with Larry McMurtry — with whom he’d just worked on The Last Picture Show — to write a screenplay. But all three of the legendary actors passed, dismissing the idea of closing the curtain on the form. McMurtry ended up adapting the script into his bestselling novel and TV mini-series Lonesome Dove, with Tommy Lee Jones in the John Wayne role, Robert Duvall in the Stewart part, and Robert Urich filling Fonda’s shoes. McMurtry then used the title (taken from the old cowboy ballad) for his Lonesome Dove sequel.

The Loves of d’Annunzio and Duse, by Orson Welles

No beloved filmmaker left more incomplete film projects than Orson Welles, but this 1952 project never made it past the screenplay stage. He wrote a script dramatizing the wild love affair of Italian actress Eleonora Duse and writer Gabriele D’Annunzio as a vehicle for, respectively, Greta Garbo and Charles Chaplin. But when both actors passed on the project, the script stalled and Welles moved on.

One Saliva Bubble, by David Lynch and Mark Frost/ The Dream of the Bovine, by David Lynch and Robert Engels

There are nearly as many unrealized Lynch movies as Welles movies; these are but two of the most intriguing, both apparently intended as broad comedies. Lynch and Frost wrote One Saliva Bubble in the late 1980s, about a year before collaborating on the script that would become Twin Peaks. It was the story of a government project that goes amok, causing the switching of identities in the small town of Newtonville, Kansas. Lynch reportedly had Steve Martin and Martin Short in mind for two of the key roles, which would have been… interesting?

Lynch wrote Dream of the Bovine, which he described as a “a really bad, stupid and repulsing comedy, but I found the whole thing just fantastic,” with Engels in 1993. It was the story of three men who used to be cows. Harry Dean Stanton was to play one of the men; Lynch got the wild idea of trying to cast Marlon Brando in one of the other roles, so Stanton made the introduction. Brando, unsurprisingly, passed on the script, calling it “completely hollow.”

Balzac, by Samuel Fuller

Renowned tough-guy raconteur and idiosyncratic filmmaker Fuller left several unproduced screenplays in his wake, including Cain and Abel, The Charge at San Juan Hill, a sci-fi take on Lysistrata called Flowers of Evil, and a Vietnam protest picture called The Rifle. But his most intriguing unmade film was a biopic of Honoré de Balzac, one of his favorite writers. From Fuller’s autobiography A Third Face: “My ball-grabbing opening had young Balzac and his mother in a runaway stagecoach, hurtling along a treacherous road next to a cliff, the future novelist struggling with the reins of the startled horses and finally saving the day. Hell, Balzac was going to be a sexy adventure picture with plenty of action!”

The Brotherhood of the Grape, by Robert Towne or Curtis Hanson

This 1977 novel by John Fante (Ask the Dust) was twice pegged for adaptation. Shortly after its publication, Robert Towne (Chinatown, Shampoo, The Last Detail) penned a screenplay adaptation, which Francis Ford Coppola planned to direct. It was one of several 1980s projects that Coppola was unable to make after the widely publicized failure of One from the Heart. But Coppola’s American Zoetrope company retained the film rights, and in the late 1980s, Curtis Hanson (who would go on to make L.A. Confidential and Wonder Boys, among others) took another pass at the script, which he hoped to direct with Burt Lancaster in the lead. But that iteration, as well, never came to pass.

Gershwin, by Paul Schrader and John Guare

As one of the most successful screenwriters of the ‘70s and ‘80s, Schrader (Blue Collar, Hardcore, American Gigolo) saw several of his scripts left unmade for various reasons; we’d love to have seen his adaptation of Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion, which he reportedly wrote for Sidney Lumet to direct with Al Pacino and Christopher Walken in the leads. But even more intriguing is this proposed 1981 project, a biopic of George Gershwin for director Martin Scorsese (who directed Schrader’s scripts of Taxi Driver and Raging Bull and, later, The Last Temptation of Christ and Bringing Out the Dead). It stalled at that point, probably due in no small part to the disappointing box office and (initial) reviews for Scorsese and Schrader’s Raging Bull. But it remained on Scorsese’s back burner for over a decade, its script later taken over by playwright John Guare (The House of Blue Leaves, Six Degrees of Separation). When Scorsese finally abandoned the project, producer Irwin Winkler let it die, instead turning his energies to the forgettable Cole Porter biopic De-Lovely, with a script from Jay Cocks (Scorsese’s Age of Innocence and Gangs of New York co-writer).

Who Killed Bambi?, by Roger Ebert

Nearly a decade after the release of their cult classic Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, moonlighting film critic Ebert and director Russ Meyer were hired by Sex Pistols manager Malcolm McLaren to create a big-screen vehicle for the Pistols, described as a kind of punk-rock Hard Day’s Night. According to Ebert (who writes about the film, in entertaining detail, here), only about a day and a half of shooting was completed before the plug was pulled (Meyer says they did four); stories vary as to whether 20th Century Fox’s skepticism or McLaren’s unpaid bills were the culprit. Either way, you can read Ebert’s script here.

Noriega, by Oliver Stone

Controversial filmmaker Stone spent years developing this biopic of Panamanian politician Manuel Noriega, hoping to shoot it in the early 1990s (while on a post-JFK hot streak) with Al Pacino — who’d starred in the Stone-scripted Scarface — in the leading role. But in May of 1994, shortly before the release of his Natural Born Killers, Stone announced that he was dropping the project; he said he couldn’t get a handle on the script, and the $40 million price tag made it “too risky” (his most recent film, Heaven and Earth, had disappointed at the box office, as had Pacino’s Carlito’s Way). Noriega’s story would ultimately be told in the 2000 TV movie Noriega: God’s Favorite (with Roger Spottiswoode directing and Bob Hoskins in the title role), after Stone and Pacino had finally collaborated, the previous year, on Any Given Sunday.

Fletch Won, by Kevin Smith

Clerks writer/director Smith was a pronounced Fletch fan — not just of the Michael Ritchie-directed Chevy Chase vehicles, but of the original series of books by Gregory McDonald, which Smith said taught him much about dialogue writing. So when the rights to the film series became available shortly after the success of Smith’s Chasing Amy, Miramax picked them up, eyeing it as a franchise. Smith penned what he called “an insanely-faithful-to-the-book” adaptation of Fletch Won, the 1985 “origin story” that showed how Irwin Fletcher became an investigative reporter, and then spent years trying to convince Miramax head Harvey Weinstein that the only man to play the young Fletch was Jason Lee. But Weinstein wouldn’t go for it, though the film was very nearly made with Smith’s other favorite leading man, Ben Affleck, in the role. Smith finally left the project in 2005, and though other filmmakers have been attached to it, the Fletch franchise remains stalled.

To the White Sea, by Joel and Ethan Coen

Following the critical success of Fargo and the surprisingly solid box office of O Brother, Where Art Thou?, the Coen Brothers were poised to make their biggest picture yet: an $80 million studio war movie, starring Brad Pitt. But being the Coen Brothers, it wasn’t that simple — their script was an adaptation of James Dickey’s novel, the story of a WWII pilot shot down over Tokyo and left to fend for himself, and as it was mostly a one-person narrative, the Coens wrote it as an all-but-silent movie. Studio heads balked at the idea, and the project ultimately fell apart, with the Coens themselves indicating it was probably dead for good. Or maybe not, since the story sounds not entirely dissimilar from the upcoming Coens-penned Unbroken — directed by Pitt’s partner Angelina Jolie.

A Day at the United Nations, by Billy Wilder and I.A.L. Diamond

We’re fudging on this one a little, since it only made it to the “treatment” stage and was never developed into a full-length screenplay. But it’s one of the most tantalizing movies ever not-made, for comedy film buffs. The story goes that while writer/director Billy Wilder was shooting The Apartment in New York, he was housed near the United Nations building, and got the idea of making a UN movie with the Marx Brothers. This was easier said than done — it had been more than a decade since their last, halfhearted picture Love Happy. But the brothers were receptive to the idea, so Wilder and his frequent collaborator I.A.L. Diamond worked up a 40-page treatment. You can read all about it here, and it’s impossible to guess if it actually would’ve worked, but the thought of Wilder (at the height of his powers) directing the Marxes is a juicy one indeed. Alas, it was not to be; shortly after the project was announced in November 1960, Harpo had a heart attack and the aging stars were unable to secure insurance for the shoot. Chico died the following year, putting the permanent kibosh on the picture.