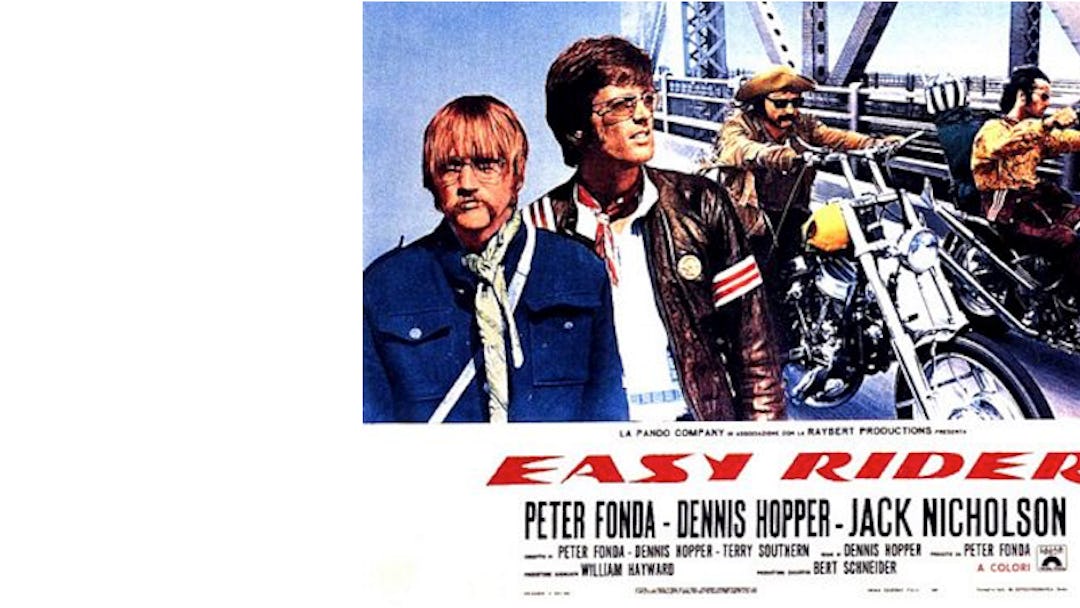

Easy Rider is nothing but trouble. Even the most casual of film fans is aware of its importance; an out-of-left-field critical and commercial smash in the summer of 1969, its unconventional approach, anti-authoritarian themes, and pop soundtrack helped set the table for the “New Hollywood” of the 1970s, and all that came after. Without Easy Rider, there would have been no Last Picture Show or Five Easy Pieces. Jack Nicholson may have never crossed over from screenwriting to screen acting. And the studios, falling to pieces after years of expensive flops, might have taken a good while longer to discover that genre-bending young filmmakers were the key to their survival. Easy Rider’s influence, its value, its consequence are irrefutable — and none of that makes it any easier to sit through. Yet saying so sounds like sneering contrarianism, if not outright trollery. You just can’t win with this one.

But that is also, I’ve realized with each hard-fought, “eat your broccoli” viewing, as simple and reductive as calling Easy Rider a “classic” and leaving it at that. It’s worth looking at the film — really looking at it — and considering it both as a bronzed cultural object and a living, breathing work of art. Each time I see it, I feel like I’m watching it wrong. I was 18 the first time, just out of high school. It was a rental from the video store where I was working, one of those movies I was “supposed to have seen” and hadn’t. I put it on after I got home from work and it literally put me to sleep. When you’re 18, nothing is more satisfying than stumbling upon a work of significance and finding reason to proclaim it unworthy (some people never age out of that desire), and I did so, telling anyone who’d listen that Easy Rider was overrated bullshit.

I returned to it a few years ago, when Criterion included it in their deluxe America Lost and Found: The BBS Story box set. By this time, I was well aware that many of my 18-year-old opinions could use some fine-tuning, and I figured it was time to give Easy Rider another shot. This time I approached it with a mixture of reverence and self-deprecation, having read my Easy Riders, Raging Bulls and watched my Decade Under the Influence and laid hands on the Criterion box as some kind of totemic object. This is one of the most important movies of our time, I told myself. If you didn’t like it, you were obviously missing something. And so I observed it dutifully, noting narrative guideposts and foregrounding symbolism, and dismissed my objections to style and pace and storytelling as ignorance — in the less pejorative sense, of someone who wasn’t alive in 1969 and thus couldn’t understand its true significance and value, not really.

But that idea doesn’t hold water either. There are plenty of films whose initially groundbreaking innovations and visual language have been replicated to a point of submersion — Citizen Kane and Halloween, two otherwise wildly different pictures, leap to mind — yet they still play, moment to moment, when you watch them today. When I took a third shot at Easy Rider this very week, determined to see it with something resembling clear eyes, the inescapable fact is that it just doesn’t play; it doesn’t consistently hold your interest.

I’m not talking about it being “dated”; that’s a broad and ultimately meaningless brush to paint with. It is set in the late 1960s, and the characters who populate it reflect that time in their appearance and speech. This is a given. The problem is not that it is filled with scenes of “far out, man” campfire philosophizing; it’s that said scenes are endless, and ultimately offer little beyond platitudes. The problem is not that there is a sequence set at an almost comically idyllic commune; it’s that the sequence is so sluggishly executed (seriously, I’ve had transatlantic flights that felt shorter than this section of the film), and its tropes and dialogue are so cliché-ridden as to play like self-parody. The problem is not that director Dennis Hopper indulges in so much film-student gimmickry; it’s that such touches succeed only in calling attention to themselves, and to their creator. (There’s a reason those stutter-cuts haven’t become part of the filmmaking grammar — it’s because they’re a really terrible way to get from one scene to another.)

But the problem with taking a purely skeptical view of Easy Rider — which is easy to do, once you start picking at the picture’s scabs — is that so much of the movie that still has a pulse, still vibrates with such manic energy that you can shut out the rest and understand why it got everyone’s hair up back in ’69. The way Hopper plucks out the single sound of the airplanes landing during the drug deal. The potent imagery of Peter Fonda stuffing all that money into his star-spangled gas tank. The punch “Born to Be Wild” still packs in that credit sequence, even after decades of imitation and parody. How Fonda wisely underplays, letting the movie come to him. And most of all, the way the movie snaps to attention when Jack Nicholson shows up halfway through — it’s intoxicated with his smirk, his drawl, and his up-for-anything disposition.

When people talk about how great Easy Rider is, I wonder if they’re choosing, deliberately or not, to only remember those things — if, in their heads, they’ve edited out the clumsy symbolism (they change the tire while the ranch hands shoe the horse because they’re the new cowboys, you see), and the simplistic villainy (there are only two kinds of reactions to Wyatt and Billy: the teenage girls who want to fuck them and the hillbillies who want to kill them — and maybe fuck them), and the nakedly schematic ending (a self-conscious feel-bad bummer that plays like a cop-out, a retreat from the self-reflection of “we blew it”).

All of which is to say that dealing with Easy Rider as a film, rather than as a Symbol of the Spirit of the 1960s or some equally reductive construct, requires some work. To seize on its flaws and dismiss the film wholesale on account of them does no one any good, aside from the puffed-up young contrarian. But to place it on a pedestal as an unimpeachable classic — and frankly, much of the film plays like Hopper flying his birdie at that very notion — does this film (and, for that matter, any film) an equal disservice.

Flavorwire is commemorating the 45th anniversary of Woodstock with Boomer Audit Week, a series of essays reevaluating touchstones of ’60s youth culture in the context of 2014. Click here to follow our coverage.