In Sigrid Nunez’s book The Last of Her Kind, the central character, Georgette, meets her troubling, troubled, wonderful friend Ann when they are both students at Barnard College in New York. I can remember, quite clearly, that school for Georgette consists of her writing a long paper, “Why The Great Gatsby Is Not a Great Book.”

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s classic figures into Nunez’s book repeatedly, with several Gatsby references peppering the narrative. Some of it is from the plot’s setup, with the dynamic between Georgette and Ann echoing Nick and Gatsby, but some of it also feels like Nunez is saying, hey Fitzgerald, top that: I’m going to write a great book that deals with women, friendship, the ’60s, racial strife, and class issues. She did — I loved The Last of Her Kind — and it feels like a book that wrestles with The Great Gatsby‘s shadow, only to come up with something sprawling, ambitious, and weirder.

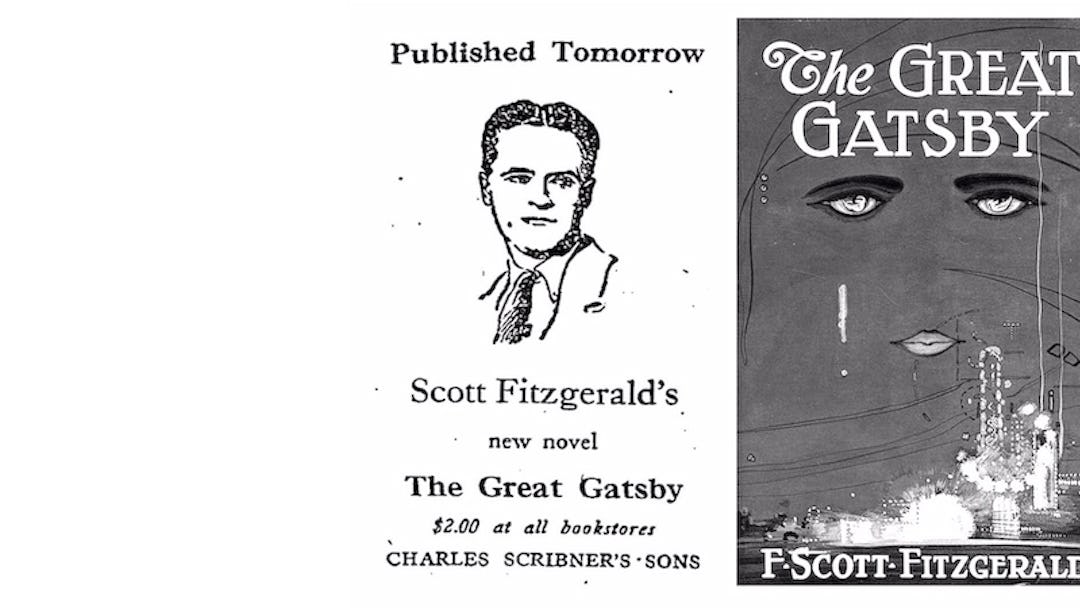

The Great Gatsby is a book that casts a long shadow: on American literature, on our “concept” of the American dream and the Great American Novel, and on the life and times of one F. Scott Fitzgerald, a writer capable of beautiful words in the midst of a life full of ecstasy and torment. The book is a rich subject, to say the least, and in the new book So We Read On: How The Great Gatsby Came to Be and Why It Endures, professor Maureen Corrigan (whose mellifluous voice should be familiar to fans of NPR’s Fresh Air, where she’s the book critic) explores why we still care about Gatsby, nearly 100 years after its initial flop run.

Corrigan is a Gatsby expert, and the book is a hybrid of biography and literary criticism. The results are all over the place: we learn that Hemingway was a dick to Fitzgerald; the main symbolism of the book was swimming and drowning, not that “green light”; part of what helped Gatsby re-emerge was that it was in the “Armed Services Editions,” an early, fascinating look at a free paperback program for soldiers during WWII. The Great Gatsby is put in more context than we ever get in school, but due to the diffuse approach, the insights don’t resonate.

She notes, specifically, that the Fitzgerald “revival,” as it comes around, periodically, is always balanced out with contrarians. Back in the ’40s, Robert Frost was quoted as shrugging over the return of Gatsby. Literary critic Leslie Fiedler compared Gatsby to “the girl we left behind.” And just last year, New York Magazine‘s book critic Kathryn Schulz wrote “Why I Despise The Great Gatsby,” where she argues:

There is the convoluted moral logic, simultaneously Romantic and Machiavellian, by which the most epically crooked character in the book is the one we are commanded to admire. There’s the command itself: the controlling need to tell us what to think, both in and about the book. There’s the blanket embrace of that great American delusion by which wealth, poverty, and class itself stem from private virtue and vice.

What gets Schulz is the novel’s passivity; the way that it presents a world like a little moral play that’s mostly concerned with the rich and how they got that way, without any of the real collusions of soul.

Throughout her book, Corrigan deploys a great amount of humorlessness when it comes to showing how she feels about Gatsby’s mainstream ascent, where the novel has become a code word for money and luxury in our modern world. She can’t help but quibble at the choice of “despise” in the Schulz piece, or to note that it went viral.

While Gatsby the novel is a fascinating text of love, literature, and the visions that we have of America, I’m not sure if Corrigan’s embrace of some of the legend behind Gatsby expands the reader’s view of it. These days, where “Gatsby” is a codeword for luxury and excess, bought up by advertisers, I’m finding that the book’s so-called contrarians, whether it’s Schulz writing for the Internet or Nunez’s big, ambitious novel, illustrate more of what makes Gatsby “Gatsby,” at least in the negative space. It’s certainly one of the Great American Novels that we should come back to again and again in our lives, but we should consider the “contrarians,” as their measured, considered objections raise more important ideas than your average Baz Luhrmann adaptation or the many, many interesting facts and truths that make up So We Read On.