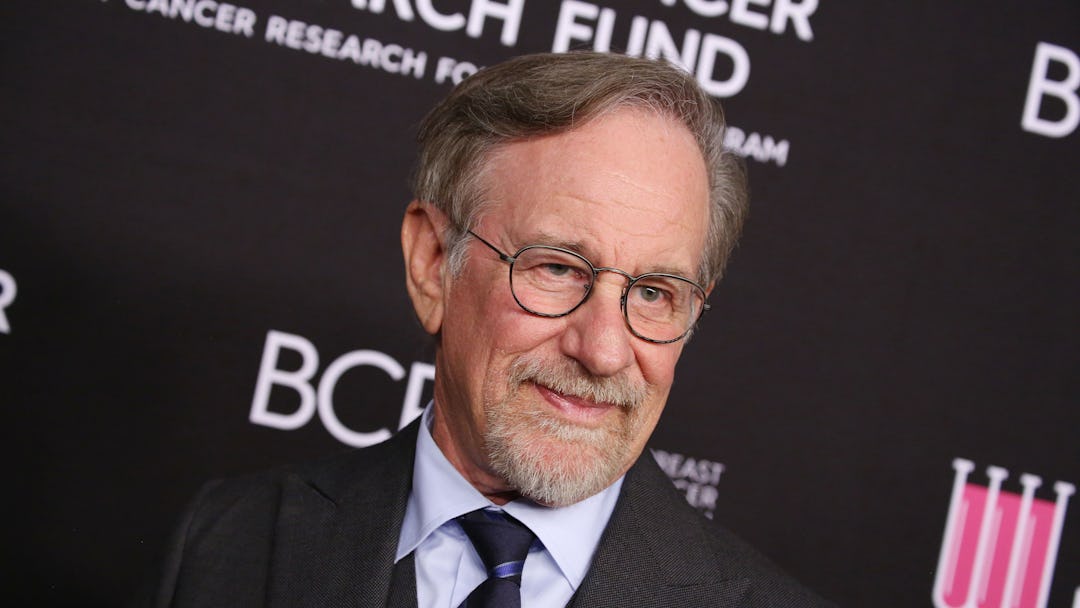

Forty years ago this week, Universal Pictures released the film adaptation of a pulpy bestseller and watched as it became a hit beyond their wildest dreams — breaking box office records, changing the movie business forever, and turning its director from a promising young hotshot into one of the most bankable filmmakers in the business. The film, as you’ve probably guessed, was Jaws, and the director was Steven Spielberg, who used that film as a launching pad into one of the most lauded (and profitable) careers in movie history. So on this anniversary of Spielberg’s ascension into the stratosphere, we look back at that career, stacking up all of his feature films (aside from his two TV-only efforts, Something Evil and Savage, which are respectively difficult and impossible to find) to date.

29. War Horse

To put you at ease: this is not one of those down-is-up rankings that sets out to provocatively boost the unloved and take down the beloved; I can assure you that the top five or so are probably exactly what you think they’ll be, though perhaps not in your particular order. And yes, I’m aware that War Horse was a well-reviewed Best Picture nominee. But everyone has their particular Spielberg kryptonite, and this is mine; it’s handsomely mounted but utterly sappy, undone left and right by its goofy solemnity and an overstuffed John Williams score that all but sits on your head and yells at you to cry. When Spielberg’s detractors talk about how cloying and maudlin and manipulative his work is, this is what they’re talking about.

28. Twilight Zone: The Movie

Or this. Spielberg’s first project coming off the whammo summer of 1982 (when he directed E.T. and produced Poltergeist) was this anthology tribute to Rod Serling’s iconic series, which Spielberg produced alongside John Landis, with both directing segments. And then they saw the picture swiped from them by less-established genre directors Joe Dante and George Miller; Landis’ opener would’ve been a misfire even if it didn’t carry the baggage of three tragic on-set deaths, and Spielberg’s piece is pure, sloppy treacle.

27. 1941

“What a mess!” Robert Stack announces midway through Spielberg’s 1979 comedy. “What a goddamn mess!” It’s a trenchant bit of inner-movie criticism for this massive pile-up, which flopped loudly in the shadows of Jaws and Close Encounters upon its initial release, but has since acquired a reputation among a certain kind of Spielberg apologist as “underrated” and “misunderstood.” But the initial impressions were right — Spielberg’s never exactly had a natural touch for comedy, and his approach here was apparently to fill the screen with activity, and have everyone scream a lot. The sense of controlled chaos is occasionally impressive, as are the inventive widescreen compositions, but generally speaking, 1941 is just big and noisy and unfunny, which shouldn’t be the case with this assemblage of SNL, SCTV, and Animal House vets. (Belushi’s pretty great, though.)

26. The Lost World: Jurassic Park

Spielberg was so intent on replicating the one-two punch of Jurassic Park and Schindler’s List, released six months apart in 1993, that when he made a sequel in 1997, he released another serious movie (Amistad) that winter too. But neither could measure up, particularly not this unfortunate retread, which boasts one great sequence (and seriously, that trailer scene, good gravy), plenty of water-treading, and an utterly insipid closing sequence of a T. Rex rampaging through San Diego, which I can only guess constituted Spielberg’s attempt to make a Godzilla movie.

25. Hook

The filmmaker’s 1991 riff on the Peter Pan story has acquired a rather sizable fan following among ‘90s kids (and BuzzFeed writers) who were exactly the right age when it hit theaters — to which I say, there’s nothing like childhood nostalgia to convince you that a tinny, flatfooted filmed deal was a masterpiece. To be sure, there are some energetic performances (Dustin Hoffman’s title turn is pretty great, and Bob Hoskins is even better as his sidekick) and a few magical touches, but for the most part, Hook is a hokey, sluggish, cluttered miscalculation.

24. War of the Worlds

There’s so much great stuff in the first hour of Spielberg’s loose adaptation of H.G. Wells’ classic that it’s easy to presume it’s going to be a great movie; the dread and fear of the attacks, the energy and momentum of the escape, the confidence with which Spielberg moves his camera, the ease and believability of the familial relationships. But the narrative slips out of the filmmaker’s grasp during the bizarre Tim Robbins interlude, and the ending — which voids the stakes and grafts on an atonal happily-ever-after that’s designed and photographed like an autumnal Gap ad — is a huge, game-changing foul.

23. Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull

Again, NOT TO BE A CONTRARIAN, but the nearly-two-decades-later fourth chapter of the Indy saga has acquired a reputation that’s far worse than the film itself. Which isn’t to say it’s without issues; the pacing is sometimes off, the reliance on CGI doesn’t mesh with the series’ established style, and Shia LaBeouf is, well, Shia LaBeouf. But it’s fun to see Harrison Ford back in the fedora and back in the frame with Karen Allen, and there’s real pleasure in these set pieces. Weakest of the series, sure — but not the disaster it’s been branded as.

22. Always

The filmmaker’s second 1989 movie — a holiday release after that summer’s Indiana Jones movie, a trend you’ll see a few times — is typically seen as inessential Spielberg, a well-intentioned but forgettable remake of Victor Fleming’s 1943 film A Guy Named Joe, one of Spielberg’s favorites. But its lightness and affability are exactly what make it so interesting, considering the heavy topics of the years ahead; he’s making a sweet, likable romance, and a pretty good one. Richard Dreyfuss (making his third and, to date, final appearance in a Spielberg picture) and Holly Hunter are aces, and John Goodman has some lovely beats in support. Not a classic, but a low-key charmer that’s worth a look.

21. Amistad

Good intentions abound in Spielberg’s 1997 story of an 1839 slave ship mutiny and its subsequent legal battle, which boasts a stunning Djimon Hounsou performance and several powerful sequences (the ship crossing sequence is as harrowing as the “Give us free!” scene is inspiring). But it’s also one of those unfortunate stories of racial struggle as seen through the eyes of heroic white people — in this case, John Quincy Adams (Anthony Hopkins, very good) and Roger Sherman Baldwin (Matthew McConaughey, not very good) — which softens the impact and renders it an occasionally ineffectual telling of a vital, important story.

20. The Terminal

Spielberg’s third pairing with Tom Hanks (and their last until the forthcoming Bridge of Spies) was this breezy flick from 2004, his first pure comedy since 1941, and a good deal more successful. It’s a loose movie — at 121 minutes, perhaps a bit too much so — and a good deal more relaxed than that earlier misfire, finding its center in a Tati-esque Hanks performance that’s all about stillness and patience. Some of it doesn’t land (most of the romantic scenes feel forced and ungainly, shoehorned into a story that didn’t need them), but The Terminal is unassuming and sweet and endlessly nice, and it’s always fun to watch Spielberg relax and take a break from the Oscar-courting epics and summer blockbusters.

19. The Adventures of Tintin

Spielberg released two movies within weeks of each other in late 2011: War Horse and this mirthful, zippy adaptation of the Belgian cartoon series. It finds the filmmaker teaming with some intriguing collaborators (Edgar Wright and Joe Cornish contributed to the screenplay; Nick Frost and Simon Pegg are among the voice talents; Peter Jackson co-produced, and apparently brought along Andy Serkis) and crafting his best adventure yarn since the heyday of Indiana Jones. The only problem is Spielberg’s use of “performance capture animation” (an inexplicable preoccupation of buddy Robert Zemekis). As usual, the technique gives his characters a weird, waxy look, their dead eyes providing a shortcut to the uncanny valley. Had he gone with traditional animation (as in the opening credits) or even live action, Tintin could’ve been one of Spielberg’s very best.

18. Munich

Spielberg can’t always get his arms around the right tone for this 2005 drama — is it a heavy drama? A shoot-’em-up thriller? A political polemic? — and the juxtaposition of jazzy, Hitchcockian globetrotting with verbose moralizing is somewhat jarring. But if it’s a difficult picture, it’s also a rewarding one, asking troubling questions, placing us in questionable circumstances, and demanding we determine, honestly, what we might do in those moments.

17. Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade

Sure, its MacGuffin (the Holy Grail) is mighty close to Raiders’ Ark of the Covenant. Yes, there’s a play-it-safe element to the storytelling that clearly reflects the mixed response to Temple of Doom. Granted, Alison Doody is clearly the least interesting of the Indy ingénues. But ya know what? When you get down to it, it’s Ford playing Indiana Jones, with Sean Connery as his dad, and sorry, it’s tough to get too hung up on the other stuff.

16. Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom

Then again, I’ve never had much trouble with Temple of Doom (aside from the shrillness, in writing and playing, of Kate Capshaw’s Willie). The darkness and even sourness at its center remains controversial, but kudos to Spielberg for choosing not to do just another mindless retread; it remains the weirdest and riskiest of the Jones pictures, eschewing the first film’s Saturday serial conventions and (as Roger Ebert notes) borrowing instead from the playbook of the impregnable fortress adventures. The rail car chase remains one of Spielberg’s finest action scenes, and while Doom can’t replicate the grinning enthusiasm of Raiders, it’s still a helluva lot of fun.

15. The Color Purple

Spielberg’s first real play for cinematic “respectability” came in the form of this 1985 adaptation of Alice Walker’s staggering book. And while it’s very, very easy to get hung up on the movie it could’ve been — the jettisoning of the novel’s sexuality still doesn’t sit well, and there’s always the question of whether a white man was the right filmmaker for this material — let us not disregard the movie Spielberg made, which is filled with warmth and empathy, tees up rage and tragedy when appropriate, and captures a Whoopi Goldberg performance (her film debut) that still astonishes.

14. Catch Me If You Can

This 2002 hit remains one of Spielberg’s most slippery bait-and-switches. It was promoted as a bouncy con-man picture, and indeed often plays like one; Leonardo DiCaprio is an appropriately charming antihero, Tom Hanks projects the right counterpoint as his boxy pursuer, and the filmmaking captures the creamy, playful thrill of the pursuit. But there’s a genuine melancholy underneath the smart suits and shiny cars, with Spielberg using the complicated paternal relationship of this con man’s story as cover for one of his most unexpectedly personal pictures.

13. The Sugarland Express

Spielberg’s films tend to focus on male protagonists, but his theatrical debut concentrated, with admirable nuance, on a woman: Lou Jean Poplin, played with adroit complexity by Goldie Hawn. The film’s extended, multi-vehicle chase scenes made it a natural extension of his TV movie breakthrough Duel, but this time, he delved deep into the personalities of those behind the wheel, and with his crowd-pleasing instincts not yet in place, he crafts a tricky and unpredictable character study, and a model of bracingly alive film craft.

12. Empire of the Sun

Spielberg’s second Serious Movie was this 1987 adaptation of J.G. Ballard’s semi-autobiographical novel. Beginning as an evocative portrait of privilege during a time of turmoil (with a stunningly good Christian Bale in the lead), this story of Shanghai in World War II becomes something of a child’s nightmare, filled with dreamlike imagery and real terror. Spielberg is taking real risks here, tonally and emotionally, and the efficiency of his visual storytelling is nearly as striking as the considerable emotional heft.

11. Schindler’s List

Many consider this Spielberg’s finest achievement, and it is an astonishingly powerful grappling with a giant subject, filled with sequences almost too difficult to bear and a trio of leading performances — by Liam Neeson, Ralph Fiennes, and Ben Kingsley — that remain their gold standard. But it’s not without its missteps (this viewer is no fan of the condescending simplicity of the “girl in red,” and there’s something just a little too neat about the feel-good documentary footage at the end), which make it less a masterpiece than an important transitional film, proving that the filmmaker could dramatize major historical moments while still reaching a mass audience.

10. Lincoln

It’s still impossible to overstate the wisdom of Spielberg and screenwriter Tony Kushner’s decision to buck even the title of this biopic, forgoing the maddeningly shallow cradle-to-grave conventions of the form and focusing instead on a short but instructive period of the 16th president’s life and work. In doing so, and thus dispensing with iconography in favor of day-to-day nitty-gritty, they managed to do the seemingly impossible: they brought the man to life, rather than merely the legend.

9. Minority Report

The best science fiction doesn’t just tell us about the future or about alien civilizations; it tells us about our present, and about ourselves. Such is the case with Spielberg’s riveting 2002 adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s short story, which isn’t just a cracklingly good procedural or a quicksilver chase; it’s also an examination of the power of police and the reliability of preventive law, and the questions it poses have only become more timely in the years since its release.

8. Duel

Spielberg’s first feature, originally seen in 1971, wasn’t meant to be much; then a television director, he was given the job of shooting a Richard Matheson script to air on ABC, and like most TV movies, he was basically supposed to turn in something that could be shot cheap and fast (13 days to shoot it, ten to edit) and could fill airtime, with proper placement for the commercials. But he came up with something so taut, gripping, and captivating, worked out with such meticulous skill and cinematic finesse, that it couldn’t just disappear into reruns and viewer memories; Universal picked it up for overseas distribution, bringing back the director for two more days of shooting, and ending up with a first-rate thriller. It quickly became Spielberg’s calling card, helping him land the Jaws gig, and its rough energy and everyday terror are just as affecting, all these years later.

7. Jurassic Park

In some ways, a Jaws-like horror/adventure was a bit of a step backwards for Spielberg circa 1993 (on his way to Schindler’s List). But the sleek professionalism and unerring instincts of the master filmmaker are part of what made Jurassic Park such a dino-sized (hahaha) hit — that, and those amazing dinosaurs, captured by the director with then-burgeoning computer effects and the proper dose of jaw-dropping awe.

6. A.I. Artificial Intelligence

Stanley Kubrick has been working on this sci-fi fairy tale for years, and had sought Spielberg’s help on it, before his death in 1999. When Spielberg took over, the results could’ve been disastrous; these were two very different filmmakers with very different sensibilities, and the film is occasionally jostled by their divergences. But in a remarkable and rather unexpected way, this unconventional collaboration brought out the best in both artists, resulting in a film that is less crowd-pleasing than Spielberg’s norm, and more emotionally open than your typical Kubrick. It’s not an easy film, but one filled with haunting imagery and thoughtful beauty.

5. Close Encounters of the Third Kind

Spielberg followed Jaws with his first exploration of one of his most durable themes: what lies beyond our world, and how we would interact with it. Richard Dreyfuss again proves a spot-on Spielberg avatar, the bookish everyman who finds himself in extraordinary circumstances, while the filmmaker creates some of his most enduring and iconic images en route to a truly stunning climax. The parade of revision and editions have made the film seem a bit of a work-in-progress, but in all of its mutations, CE3K finds the filmmaker confident, locked in, and humming.

4. Saving Private Ryan

The justifiably celebrated Omaha Beach sequence that opens Spielberg’s 1998 WWII epic remains one of his most astonishing pieces of filmmaking — shot with you-are-there-immediacy and using only the barest of dialogue, it is visceral war cinema at its most harrowing and horrifying. But the film that follows is no slouch either, embracing the conventions of countless men-on-a-mission pictures, and then pushing into the kind of tear-jerking power and reflection that such movies often eschewed.

3. E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial

In 1982, Spielberg found his greatest commercial and critical success with the simple story of a boy and his alien. But his approach was anything but basic: with a sophisticated style that told the story from ground level (literally — he framed most of the shots from his young protagonists’ eye lines), Spielberg crafted one of the most disarmingly evocative snapshots of childhood ever put to celluloid, and created an enduring catchphrase to boot.

2. Raiders of the Lost Ark

Director Spielberg and producer George Lucas, pals since their film-brat days, teamed professionally for the first time to make this valentine to the Saturday serials that thrilled them as youths. The film they created pulses with the childlike glee of sitting in those movie palaces, grinning in wide-eyed anticipation of your hero’s next adventure; it just goes and goes, propelled by an enchanting sense of intoxicating fun, simultaneously honoring iconography and building one of its own.

1. Jaws

Your mileage may vary, but as far as this viewer is concerned, Spielberg’s first giant hit is still his best. Every frame is beautifully constructed (Pauline Kael, quoting an unnamed director, sometimes reported as Hitchcock: “He must have never seen a play; he’s the first one of us who doesn’t think in terms of the proscenium arch”), not a single shot is wasted, every character is unique yet carefully considered in relation to each other character, and the music is, well, the music. It’s the kind of movie where every moment plays like something out of a “cinema’s greatest hits” reel: the first shark attack, the Brody reverse-zoom, the lurch towards the chum, and, holy of holies, Robert Shaw’s Indianapolis monologue. Jaws is perfect — and not in the boring way that carefully controlled and lifeless movies strive to be perfect (because we know how imperfect its production was), but because everything in it came out just right, and you can’t imagine it any other way.