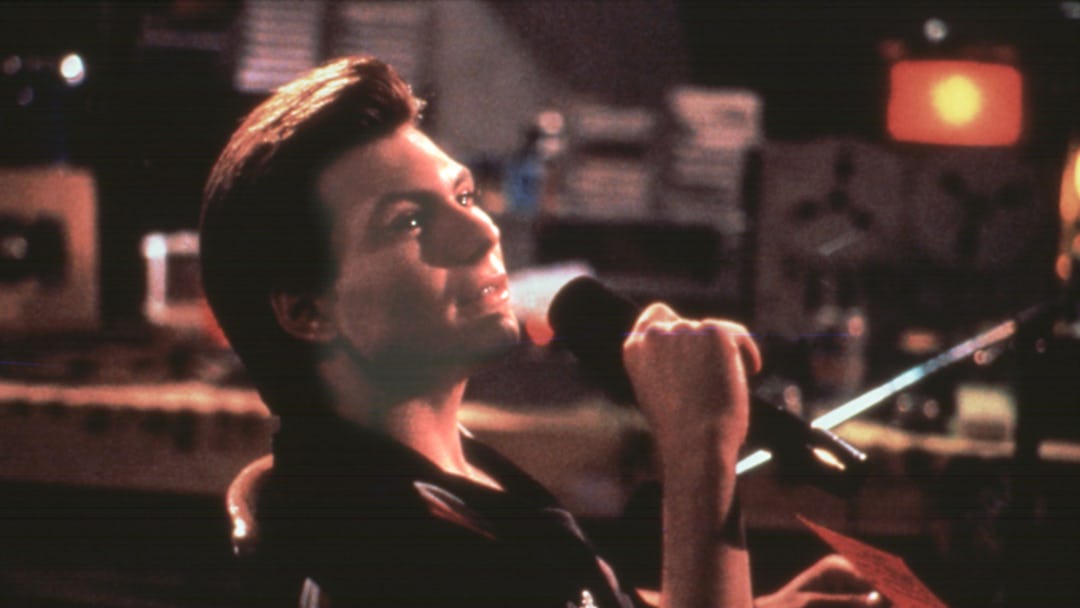

This weekend marked the 25th anniversary of the release of Allan Moyle’s Pump Up the Volume, and in all the obvious ways, it shows that age: the music, the clothes, the cars, the references. More than anything, its 1990-ness is manifested in the story itself, in which a high school misfit (Christian Slater) becomes an anonymous celebrity via his nightly broadcasts on a short-wave radio (initially purchased “so I could talk to my friends back east” — remember when long distance was a thing?). But Volume is no quaint time capsule; the details may be period, but in its broad strokes, Moyle’s movie was strikingly prescient about how we — particularly the youngest of us — both consume and create media.

So some context is necessary. In 1990, radio and MTV were still pretty much the only way people heard new music; provocative commentary was mostly confined to the pages of underground publications. Dangerous ideas — whether put to the page or set to music — were still a rare commodity, a secret whispered in polite company, so when a tape of “Happy Harry Hard-On” is passed on a school bus with the gleeful message that “he played Ice-T last night,” it means something. The mere fact that his pirate show is on the airwaves in his Arizona suburb is an act of provocation, echoed when students, inspired by his rebelliousness, play tapes of it in class (“It’s the third tape this week,” fumes the shop teacher).

As time passed, of course, such esoteric pipelines would become obsolete. Two years after Pump Up the Volume’s release, America Online would launch their Windows platform, eventually bringing Internet access to homes across the country; by the end of the decade, most of Harry’s listeners would’ve abandoned terrestrial radio altogether, getting their fix of free music from Napster and, today, via Spotify.

And when Moyle’s camera lovingly tilts up the stack of Harry’s tapes — Jesus & Mary Chain, Henry Rollins, the Pixies, the aforementioned Ice-T, “JFK Speech,” and Beethoven — it’s like a prototype for a Spotify playlist, and it serves the same function: at that early point in the picture, before we’ve even seen our protagonist (for the first five minutes, he’s only a voice in the night), he is his taste. This is curation as persona, the notion that you are what you like — always a component in the version of ourselves that we presented to the world, but even more vital in an age where online identity (and all the “likes” it entails) is the most frequent means of introduction.

So the songs that he plays — Leonard Cohen, Beastie Boys, Bad Brains — are as important as the words he says, if not more so. His monologues are a mix of Howard Stern-like dirty talk (again, a reminder that there was a time when real filth wasn’t just available at a click of a mouse), rabble-rousing, and teen angst. Writer/director Moyle undoubtedly realized early on that it’d be difficult to make a movie about a radio show cinematic, and his solution is simple but elegant: lots of images of people listening, and asking each other if they’re listening, and finding the spots with the best reception to listen from. And if you can’t leave the house, you call a friend who has good reception, and they’ll put the phone up to the radio (primitive Periscope, that).

Were Pump Up the Volume made at a later date, Harry wouldn’t do a radio show; nobody’s listening to radio anymore, at least at the age of his target audience (“Society is mutating so rapidly that anybody over the age of 20 really has no idea!” he remarks, not entirely inaccurately). Maybe he’d have a LiveJournal or a MySpace page; maybe he’d have a blog or an Instagram account; maybe he’d put his searching monologues on YouTube or a podcast. Whatever the case, in the years that followed Volume’s release, the methods of becoming “a voice [that] can just go somewhere, uninvited” grew infinitely cheaper and easier and more varied — though, as a result, it also became much more difficult to stand out as one of those voices, simply because there’s so much din and clatter to speak over. (There’s also an argument to be made that the careful cultivation of our social media circles means fewer “uninvited” voices are heard.)

And if we’re being honest, we shouldn’t overstate the power of his message — this is, after all, a movie that opens with the question, “Did you ever get the feeling that everything in the United States is completely fucked up?” From there, it often veers into pronouncements of bland suburban ennui and boilerplate teen malaise like, “There’s nothing to look forward to and no one to look up to” and “Everywhere I look, someone’s gettin’ butt-surfed by the system.” As a movie, Pump Up the Volume is a lot like a teenager: at times unbearably self-important and pretentious (Nora’s poems, good lord), yet undeniably, and admirably, earnest.

Greil Marcus got at this a bit when he wrote about the movie a couple of years ago in his book on the Doors: “In a certain way Pump Up the Volume is no more than a 1990s version of a 1950s prom-crisis movie: the kids want to have a rock ’n’ roll band at the big dance and the adults won’t let them; at the end Bill Haley and the Comets show up, looking older than the parents, and everything turns out all right.” And what Marcus calls the “mandated melodrama” of its ending — in which Harry’s final broadcast goes mobile, with the FCC in hot pursuit — illustrates the picture’s ultimate period touch, because it was set at a time when that agency actually could take your voice away. What Pump Up the Volume predicted (particularly in its closing moments, a soundtrack of other voices taking to the airwaves Harry has vacated) was an era where such gatekeepers weren’t villainous, but merely irrelevant.