Wes Craven’s Scream wasn’t supposed to be a smash. When it opened in December of 1996, in the midst of a particularly crowded holiday movie season, it was only on 1400 screens; it came in fourth for the weekend, grossing a respectable but unspectacular $6.9 million. But then, over the next several weeks, it did something movies just don’t do anymore: it kept topping itself. Then and especially now, hit movies open huge, drop off quickly, and disappear shortly thereafter; Scream kept adding screens and making more money, ultimately grossing over $100 million without ever topping the weekly box office chart.

It was the definition of a sleeper hit, an honest-to-God word-of-mouth sensation that kept performing because people kept talking about how great it was, turning up to see it, and then seeing it again. It was a game-changer for the horror genre — much as Pulp Fiction, another Miramax-financed smash, had been for crime pictures two years earlier. Like Fiction, Scream was witty, sharp, and gleefully self-aware. And like Fiction, Scream was loaded with references, homages, and shout-outs to the genre it was both sending up and contributing to. For moviegoers who were the right age (old enough to see it, young enough to have missed the early-‘80s horror boom), Scream was a gateway drug, and Wes Craven was their dealer.

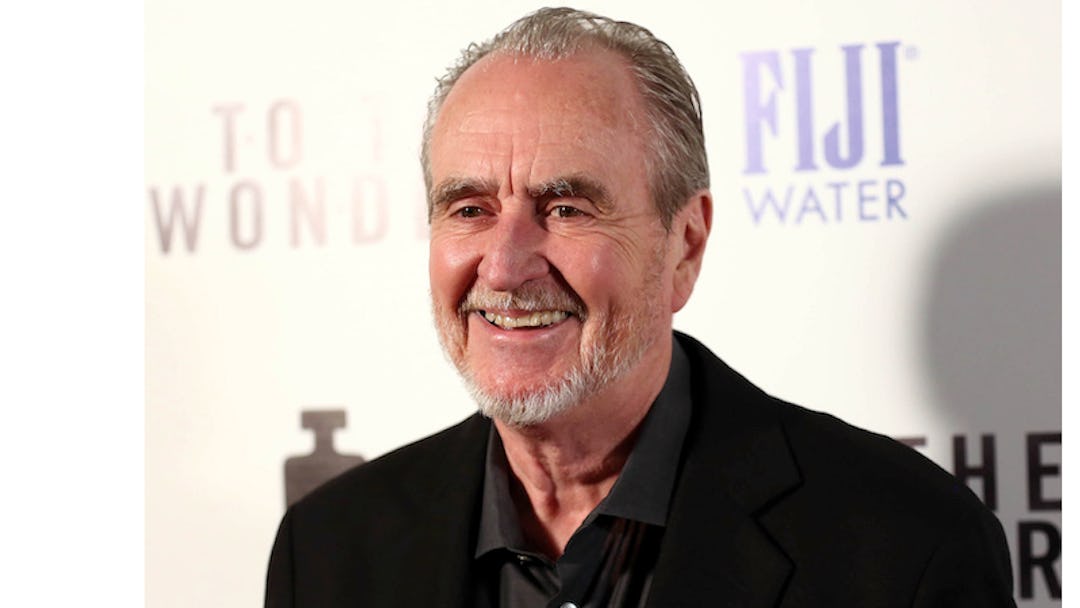

And this is why the filmmaker’s death last night has struck such a chord among movie lovers in general and horror aficionados in particular: because, for many of them, Scream was an entry point. They watched it and re-watched it, in theaters and on home video, and then followed up by seeing Halloween (which is referenced extensively and seen in clips), or Craven’s Nightmare on Elm Street (mentioned via a sly in-joke or two), or Friday the 13th or Carrie or I Spit on Your Grave or Prom Night (which all get name-checked in dialogue). Horror movies weren’t exactly in a golden period in the mid-‘90s; Scream made them cool again, and if you wanted to know and understand “the rules,” you had to know your history. Craven was a teacher before he was a filmmaker, but in films like Scream, he returned to that earlier role; his “students” became the horror geeks of today, and, quite often, its next generation of directors as well. (As Edgar Wright writes, “I vividly remember seeing this opening weekend in London and saying out loud ‘That’s the kind of movie I want to make.’”)

Much of this is as tied to Kevin Williamson’s clever screenplay as to Craven’s direction, but the filmmaker’s contribution to the picture can’t be understated. Not only had he dipped into the meta-horror waters himself with 1994’s New Nightmare (a vastly underrated picture that Craven also wrote, returning to the Freddy character that made him famous and making a film that was, in many ways, about that return); his name above the title bestowed Scream a surplus of street cred. Most importantly, Craven adroitly struck a vital balance of smirky commentary and legitimate scares. He was willing to send up the conventions, but (unlike unsuccessful horror spoofs of the Student Bodies and Saturday the 14th ilk) he was still going to deliver them. Like Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein , its clearest ancestor, Scream aimed to both make us laugh and jump, often at the same time.

Craven’s death came as more of a shock than perhaps it should have been — after all, the man was 76 years old and lived a rich, full life, chucking a comfortable existence as a university professor (he held a master’s in Philosophy and Writing from Johns Hopkins) to become a filmmaker, initially working under pseudonyms in porn before graduating to low-budget exploitation movies like Last House on the Left and The Hills Have Eyes. 1984’s Nightmare on Elm Street made him a marquee name, but he continued to experiment, tinkering in straight-up thrillers, genre as sociopolitical commentary, comedy, and (most shockingly) a Meryl Streep drama. If anything, he seemed to pass before his time because the vibrancy of his genre films made him seem perpetually younger than he was. But, like the horrifying heads popping out Freddy’s chest in Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors, the spawn of Craven are out there, doing their thing, keeping his nightmares alive.