Tuesday marks the 20th anniversary of the release of Twister, and don’t worry, this is not some sort of rhapsodic commemorative celebration; be honest, when was the last time you even though fondly of Twister, much less watched it? Yet it’s a date worth marking for what Twister was, then and now – not a significant cinematic achievement, but a big fucking event. Summer has always been where studios sent their event movies, of course. But in many ways, the big attractions of May-August 1996 pointed the way towards the modern movie summer.

First and foremost, there was the significance of its release, early in the month of May. This was well before the Memorial Day weekend that had, until recent years, marked the kick-off of summer movie season; once upon a time, early May was considered a fairly dead zone. Studios would frequently place their big movies on Memorial Day weekend and let them battle it out (as Backdraft, Thelma and Louise, and Hudson Hawk did over Memorial Day weekend 1991). But in 1992, Warner Brothers scheduled Lethal Weapon 3 on May 15 to avoid a Memorial Day weekend faceoff with Alien 3 – and ended up using that jump-start to out-gross its fellow sequel. Warner Brothers was also behind Twister, and went with a similar strategy in ’96, as Paramount had called dibs on the Memorial Day weekend for the Tom Cruise-fronted film version of Mission: Impossible.

And what did they have to sell? Twister didn’t boast big stars; sure, people knew Helen Hunt and Bill Paxton, but they weren’t exactly box office draws. It had the director of a big summer hit from 1994 (Speed’s Jan DeBont) and the writer of a big summer hit from 1993 (Jurassic Park’s Michael Crichton), but again, those names didn’t mean a whole lot to Joe Moviegoer. No, what Twister had was a high concept, and a killer trailer. You could sell it in two simple words, “killer tornadoes” (just as you could sell Crichton’s Jurassic Park with “killer dinosaurs”). And its trailer, a ubiquitous preview in theaters throughout the spring, didn’t care about plot or stars (Paxton and Hunt don’t even appear). It featured a random family of potential victims and narrator promising nature going “completely, randomly mad,” and was as much aural as visual, punctuating its black screen with eerily effective lightning flashes of weather chaos and panic.

Its closing image, of a tractor wheel careening straight into the camera, was soon complemented by TV ads showcasing a shot of the tornado tossing a mooing cow. If you polled moviegoers that May weekend in 1996 and asked who they were there to see, most would’ve probably named that cow. The strategy worked – Twister started summer movie season even earlier than usual, bringing in a startling $41 million in its opening weekend. (This was a big number for 1996.) It wound up pulling down $241 million domestic – $60 million more than Mission: Impossible, in spite of the Cruise factor.

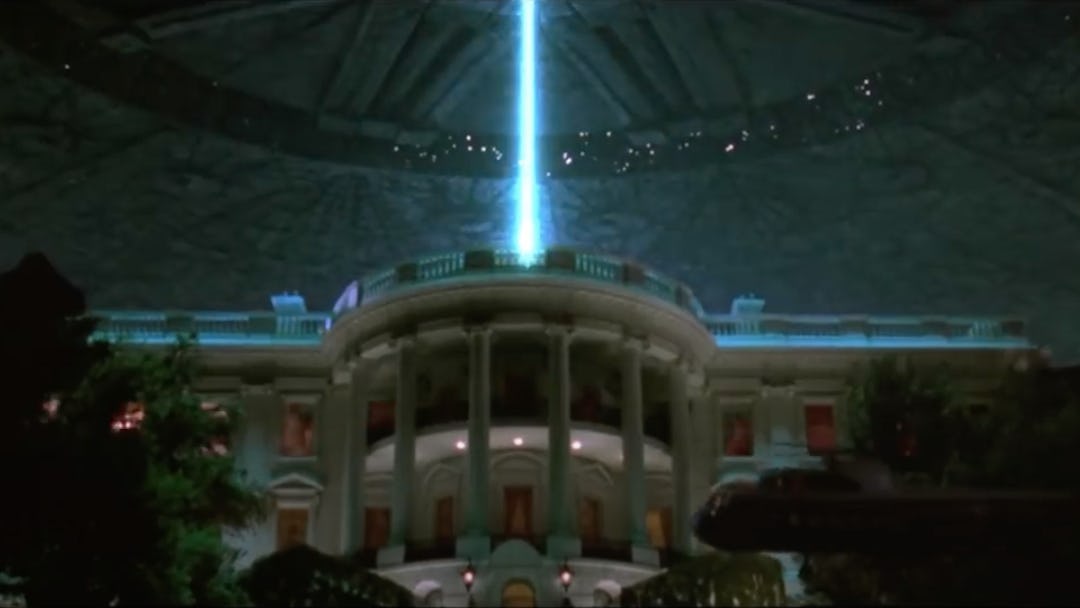

That was only the second biggest tally of the year, though; the biggest movie of 1996, summer or otherwise, was Independence Day. And just as the big attraction of Twister was the flying cow, the big draw for Independence Day was not Will Smith (who was still on the ascent, with only one big movie, 1995’s Bad Boys, to his name) or Jeff Goldblum, but an exploding White House. That key image of the ad campaign for Independence Day – or ID4, as it was quickly branded – was unveiled during the film’s Super Bowl XXX commercial that January, which meant that by the time of its July 3rd release, it had been knocking around the public consciousness for half a year.

You can spend an entire historical essay unpacking the appeal of that image – this release came during Bill Clinton’s second presidential campaign, and that administration wasn’t exactly known for its affable opposition. But the packaging of the movie was its key. Its release date was right there in the title, a reminder with every poster, bus ad, TV spot, and gaze-at-the-skies trailer that the aliens were coming to the multiplex over Fourth of July weekend. The movie was so ubiquitous, in fact, that there almost seemed a subtextual tie to the holiday’s patriotism. This wasn’t just a movie that was available to you – it was a movie that it was your duty as an American to see. Or, as MST3K’s Mike Nelson wrote at the time of these “Big Gulp-style films,” “They’re Must-See movies. Not to see them is to risk revocation of citizenship and eventual deportation.”

And that urgency would come to define not only summer movie season, but studio filmmaking in general. Audiences dutifully attend the latest Marvel effort because it is the Movie To See; they’ll even drag themselves to a movie they’ve been assured they’ll hate, simply to have seen the thing that everyone’s seeing. In earlier summers, the big hits were usually packaged the old-fashioned way: here’s a big star or franchise you know, here’s a high concept, we’ll play it all summer. So audiences turned out for Batman Forever (1995), Forrest Gump (1994), Batman Returns (1992), Terminator 2 (1991), Coming to America (1988), Beverly Hills Cop II (1987), Top Gun (1986) – you get the idea. But there were occasional anomalies: Batman in 1989, a smash hit less about star power than marketing and branding. Jurassic Park in 1993, a high concept from a name director that faced off against a seemingly sure-fire Arnold Schwarzenegger vehicle, and dusted it.

There were big, star-driven hits in the summer of 1996: The Rock, The Nutty Professor, A Time to Kill, Phenomenon. But many of those seemingly sure bets disappointed (Schwarzenegger’s Eraser, Robin Williams’ Jack, Jim Carrey’s Cable Guy) or tanked outright (Demi Moore’s Striptease, Robert De Niro’s The Fan, Kurt Russell’s Escape from L.A.). Twister and ID4 proved you didn’t need big stars for a big summer hit – you just needed to stake out a date, make a good trailer, and sell the shit out of it, preferably on a record-breaking opening weekend. And in today’s movie marketing environment, wherein studios breathlessly release casting announcements, “first stills,” “motion posters,” and teasers for trailers (aka commercials for commercials) to fan sites that eagerly lap it all up and copy-paste-publish every scrap, they’re still running the same play.