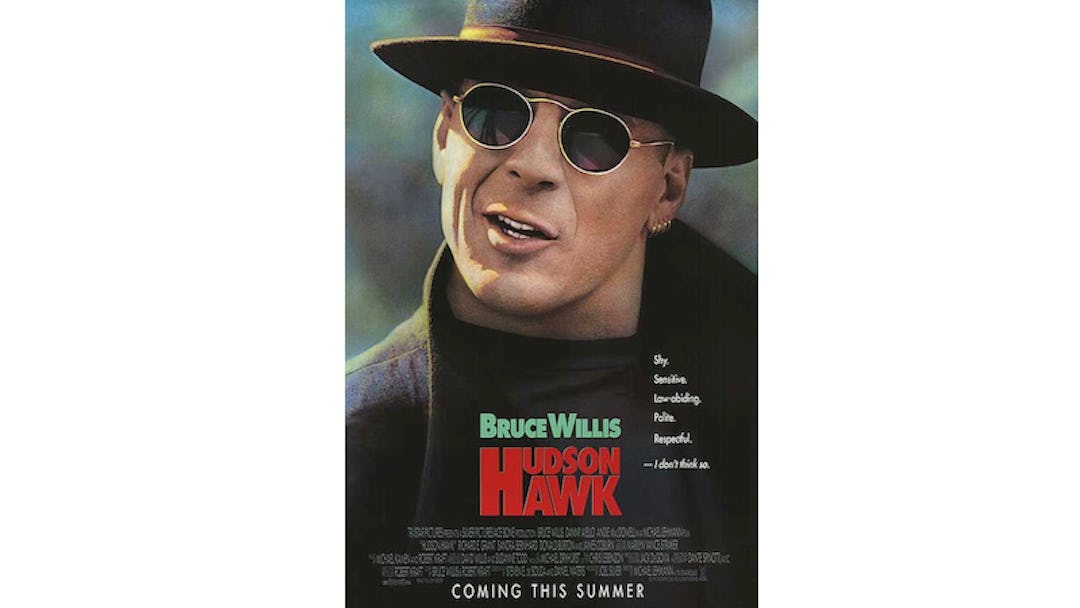

Twenty-five years ago this week, a motion picture was released that dominated popular culture, and remains a touchstone in American cinema. A rare combination of thinker and crowd-pleaser, this genre-buster was both a commercial and critical success, grossing $45 million domestic and nabbing six Oscar nominations (and one win). That movie, of course, was Thelma & Louise, and if you’d like to read some reflections on that groundbreaking picture upon this quarter-century anniversary, there are plenty of them waiting for you. Yet that very same Memorial Day weekend, another big summer movie debuted in American cinemas – opening bigger than Thelma, in fact, though its fortunes would fall quickly. Yet that movie looked like one of the summer’s sure things: a globe-trotting adventure from one of Hollywood’s biggest stars and most reliable producers, from an exciting young director. It was called Hudson Hawk.

The legacies of the two films (or, for that matter, the weekend’s #1 movie at the box office, Backdraft) aren’t even close. Within days of its debut, Hudson Hawk had become the new Ishtar – shorthand for a certain kind of cinematic failure, wherein out-of-control egos, budgets, and production result in massive misfires that are rejected loudly and disdainfully by both critics and audiences. Yet it has its defenders (just about every film with this type of reputation does); when I saw the film that weekend late in my freshman year of high school, I was one of them. A recent return viewing revealed (you may want to sit down for this) I might’ve been wrong.

All consideration of Hudson Hawk must be framed by one simple definition: this is a Bruce Willis vanity project. Jersey’s second-favorite son had finally found his big break in the form of Moonlighting, the four-season TV comedy/mystery series, midway through the previous decade, but it took a couple tries to translate that breakthrough into movie stardom; his first two starring vehicles, the Blake Edwards pictures Blind Date and Sunset, had tanked, so it was a surprise when the wisecracking comic actor fronted the action hit Die Hard. But it was a smash in the summer of 1988; two years later, he starred in Die Hard 2, which outgrossed the original by nearly $100 million worldwide.

Those films were packaged by Joel Silver, the rising Hollywood super-producer behind Lethal Weapon, Predator, and (snort) Road House. And thus Willis went to Silver with his passion project, a loony idea he’d cooked up a decade earlier with musician Robert Kraft, back when Bruce was but a struggling actor/bartender, and they co-wrote a song about a cat burglar called “the Hudson Hawk” and his buddy Tommy Five-Tone. Willis and Kraft get a “story by” credit on Hudson Hawk (the first and last writing credit for either man); the script is credited to Die Hard screenwriter Steven E. de Souza and Daniel Waters, who penned Heathers, the debut film of Hudson Hawk director Michael Lehmann.

The film they cooked up is a bizarre mishmash of heist picture, action extravaganza, and fairy tale. We meet Willis’ title character after a lengthy (and I do mean lengthy) storybook-style introduction to Leonardo da Vinci, and the secret gold-conversion machine that is the movie’s MacGuffin. Then it’s a 500-year jump to world-famous cat burglar Hawk’s release from Sing-Sing, clad in a vest, coat, fedora, and smirk (to a sax and finger-snap score, cool daddy-o), and though all he wants is to drink a cappuccino – one of the picture’s less fruitful running gags – he is immediately drafted and/or blackmailed into swiping a da Vinci horse from an art museum, which ends up being the first of three da Vinci treasures with the hidden pieces required to make that gold machine work. (There’s a healthy dose of pre-Dan Brown da Vinci/Vatican conspiracy theory-ing at work in Hudson Hawk, which is about the only element ahead of its time.)

It’s easy, with the benefit of hindsight, to see how Hudson Hawk appealed to 15-year-old me, since it so often plays like a catalogue of things uncool ‘80s kids would want to do in a movie: pull heists, romance a supermodel, slide down a suspended wire, blow things up, etc. Yet this also pinpoints the film’s fundamental miscalculation: I had to sneak into it, since de Souza and Waters’ script is peppered with so many four-letter words, Hawk ended up with an incongruent R-rating. In other words, the very audience most likely to appreciate its combination of goofball humor and mindless violence was the audience that couldn’t buy a ticket to see it. (The original trailers, which played down the humor and played up the action and thus deceived the opening weekend audiences who could buy a ticket, didn’t help.)

And let’s be clear: Hudson Hawk is, by most reasonable standards, a pretty bad movie. Its plotting is nonsense, its secondary characters are dopey, its slapstick superspy elements are filled with unfortunate echoes of Bill Cosby’s similarly self-originated 1987 bomb Leonard Part 6, there are way too many moments of flabby-cheeked electrocution and other hallmarks of people “trying to be funny,” and the one-liners are almost surreal in their terribleness (the nadir: a climactic decapitation prompts our Bruce to spout, “You won’t be attending that hat convention in July!”). And it features a supporting performance by Andie MacDowell, as a lusty nun who spends the climax doing wacky dolphin noises, that is awe-inspiring in its badness (even for Andie MacDowell).

Hawk’s slipshod unevenness was at least partially due its troubled production, during which Willis and director Lehman reportedly clashed repeatedly and Willis caused extensive delays with his daily suggestions for improvements (this isn’t hard to buy; it’s hard to properly describe how much of the film feels like the result of someone shrugging, “It’s what Bruce wants”). The film went over schedule and over budget, landing at $65 million, which then seemed like an exorbitant figure (it was a very different time), a huge loss considering its eventual, anemic $17 million domestic take. And, of course, poor Lehmann took the blunt of the blame; he made a few more features, but has mostly worked in television since Hawk’s loud combustion.

But Willis didn’t get away from this one clean. The first chink in his movie-star armor had appeared the previous Christmas, via a supporting role in Brian De Palma’s flop adaptation of Bonfire of the Vanities, but no one really blamed him for that film’s failure. On this one, he couldn’t blame anyone but himself. He rebounded reasonably well, with a modest hit the following Christmas (the Silver-produced Last Boy Scout), but the ‘90s would be an up-and-down era for Willis, with a Striking Distance or Color of Night for every 12 Monkeys or Fifth Element. He’d ended the previous decade perched atop the movie star pile, alongside his Planet Hollywood partners Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger, but their reigns were coming to an end; two weeks before Hudson Hawk, Stallone had failed with his own attempt to branch into screwball comedy with Oscar, and though Schwarzenegger ended up with the summer’s biggest hit in Terminator 2, he’d have a loud flop two summers later with another failed comedy, Last Action Hero.

Yet you have to give Hudson Hawk this much: in contrast to your typical summer blockbuster, then or now, at least it’s got some personality. The heist scenes are playful fun, thanks to the silly but enjoyable conceit that Hawk and partner Tommy Five-Tone (Danny Aiello, great as usual) keep time by singing pop songs. There’s an inventive, energetic action scene in which Willis hangs from the back of an ambulance by a bedsheet as it charges across the Brooklyn Bridge. Lehmann throws in funny asides here and there, like the Vatican guard who pours pasta from his thermos. And as the story’s weirdo super-villains, Richard E. Grant and Sandra Bernhard seem to be competing to see who can chew the most scenery (I’ll call it a draw). None of this means it works – but it does feel like those scathing reviews were bit of an overreaction, or at least a dogpile. Hudson Hawk tries to be light and flip and hip and weird, and if it only really pulls of the last one, that’s more than most big-budget star vehicles even try.

Hudson Hawk is available for rental on Amazon, iTunes, and the usual platforms.