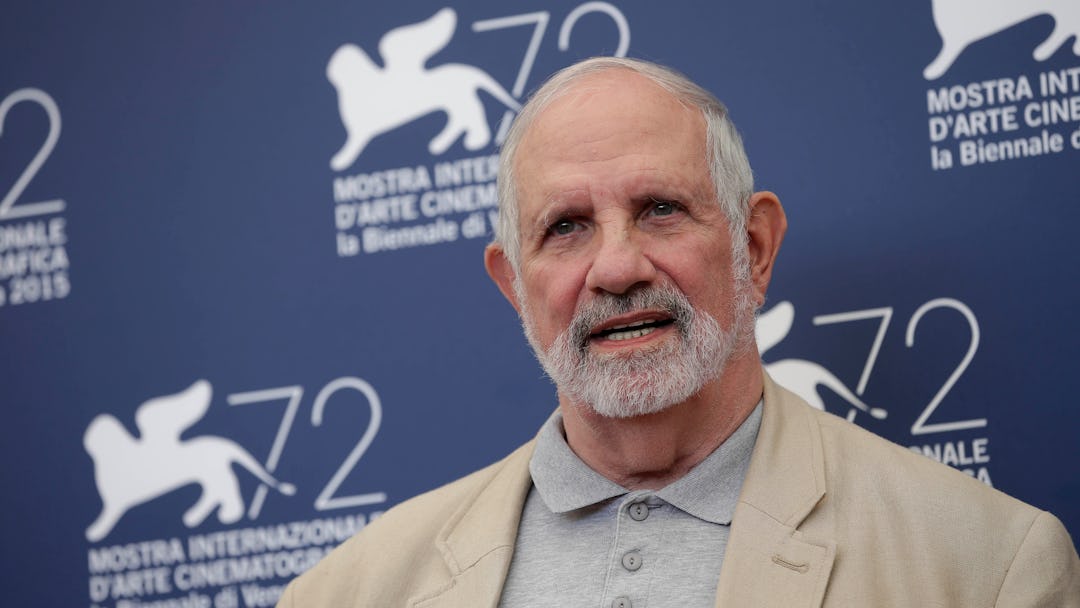

New American Cinema icon Brian De Palma is being celebrated at the Metrograph through June 30 in a new retrospective screening series. “Loved and loathed with equal fervency over the course of his amazing five-decade career, this singular American artist is a revolutionary and a rascal, an intellectual disguised as a peddler of garish Hollywood entertainment,” writes the movie house. Roger Ebert once wrote of the great visual stylist:

The ads for DePalma’s Dressed to Kill describe him as ‘the master of the macabre,’ which is no more immodest, I suppose, than the ads that described Hitchcock as ‘the master of suspense.’ DePalma is not yet an artist of Hitchcock’s stature, but he does earn the right to a comparison, especially after his deliberately Hitchcockian films Sisters and Obsession. He places his emphasis on the same things that obsessed Hitchcock: precise camera movements, meticulously selected visual details, characters seen as types rather than personalities, and violence as a sudden interruption of the most mundane situations.

Here’s what De Palma has to say about making movies within the studio system, shooting sex scenes, and our culture of remakes and sequels.

“We all wanted to get into the studio system. I was the most iconoclastic of the group who was most disenchanted with the studio system, because it had a really corrosive effect on what you did. They basically want you to duplicate the same thing over and over again. I always felt that was not good for an artist. I would fall in and out of the studio system. But you need to make hits in order to make movies. So I would go in and make a hit, be able to make a couple of weird movies, then have to start over again.”

“I can’t imagine making a studio movie now. The whole system’s changed so much because of the effect of cable television and all the cable stations making their own series. They’re really into writers and producers, which is like the old studio system. The directors came in, directed, and were sent off. That’s what you’re getting with all these television projects.”

“With young directors, you can give them the advantage of your experience, but at the end of the day, they’re working in a different world. They’ve come up in the Sundance generation and they’re used to making inexpensive movies with very personal stories. It doesn’t bother them that it takes two or three years to make a movie. They were never part of the era where you had to make a hit — a big hit.”

“Directors are desperate for friendship from other directors they respect.”

“Making movies is not some very organic development. You’re at a certain time in your life with twenty thousand reasons to make that decision. At a different time, you wouldn’t make that same decision. It’s where you are in your career, in your life.”

“I’m not interested in a lot of talk. Talk to me is very boring and a lot of people just put that up there all the time. You have many films with these long character scenes, with extremely in-depth analysis, and what you have is a lot of characters sitting around talking to each other. Which does little to excite me in terms of the possibilities of what you can do with cinema. So I have those sequences in when they’re necessary, but I certainly don’t structure my film around them. And most of cinema today is driven by television, which is all talk – I tend to be the counterprogramming director.”

“So much of shooting sex scenes in movies you a see are naked people sort of humping each other on a bed, shot in the most unflattering way just because they happen to be naked and mimicking making love. They don’t really dramatize their particular sexual attraction to each other. And it’s very difficult. You have to find a way, a visual way to approach scenes like that.”

“I’m astounded there aren’t more American political films. I’m amazed, when you can make movies for nothing, there are not people out there making these incredibly angry anti-war movies. How come?”

“I think traditional noir doesn’t work in contemporary storytelling because we don’t live in that world anymore.”

“The real trouble with film school is that the people teaching are so far out of the industry that they don’t give the students an idea of what’s happening.”

“The biggest mistake in student films is that they are usually cast so badly, with friends and people the directors know. Actually you can cover a lot of bad direction with good acting.”

“We were very lucky in our generation. We got final cut. We were in the era of the director superstar. Very few directors have final cut today. Obviously Spielberg does and Scorsese, but there aren’t too many. And the new directors are constantly not getting final cut so you have to battle with the studios to make sure that they don’t alter your movie. You can’t make very controversial movies.”

“I don’t think morality applies to art. It’s a ludicrous idea. I mean, what is the morality of a still life? I don’t think there’s good or bad fruit in the bowl.”

“You really are as hot as your last movie. And it goes away really quickly.”

“With the advent of video and the fact that you can make movies for practically nothing now, I think that’s a big change. In my day, you had to raise thousands or hundred thousands dollars to do a feature, and that’s not the case today. Now you can make it for nothing, the case is you gotta get people to see it: Submit it to a lot of film festivals, and if your movie is really good… It gives you a tremendous amount of freedom, and there are no more excuses about money. In order to make a movie today, you basically need a good script, the ability to cast it correctly, and then you go out and shoot it and show what you can do, it’s very much like writing a novel. But if you can’t do that, you’re not going to fare very well.”

“The great directors of the ’40s and ’50s were making two or three pictures a year. You don’t get better sitting in your trailer thinking about it.”

“You don’t want to fall into the rut of recreating your last hit no matter what the genre happens to be. You don’t want to make four Batmans or ten Spidermans just because you can get a huge audience to come see it and make a bit more money that you don’t need.”

“I mean when you take something from another filmmaker, build on it, and make it your own, I think it’s terrific. Tarantino’s obviously done it many times and I’m fascinated to see that evolves in other filmmakers.”

“I don’t think we can be that erotic anymore on the screen. We can’t compete with cable. It’s kind of amazing. We can’t do the kind of nudity they do on cable. I don’t know what’s comparable to an X these days, but you’d get in a lot of trouble doing that stuff they do on cable on the big screen. Eroticism and pornography have sort of gone to cable television and the web, and I don’t know if you can do much of it in movies anymore. You can only be very suggestive.”

“If you are making genre movies you cannot refuse to shoot the obligatory scenes: how do we get from A to B to C to D. But some directors feel that they are just boring parts because they are plot and who wants to hear about that — let’s get on with the stylistic business. It’s great to be a stylist, and I really like that, but on the other hand you cannot refuse to pay attention to the conventions you are working with. Make a new form and be Fellini, but then don’t try to be Don Siegel. I strongly believe there are reasons for genre forms and there are reasons that make them work. And if you ignore all the tenets of the form you are going to have something else which isn’t going to be that genre. But if you are going to avoid telling stories, then you had better come up with another way to make a movie last 90 minutes because it becomes difficult any other way. Granted there are some genius directors who can get away with it, but by and large it makes me angry to see a good, major director subordinate the content of an expository scene to style so that you can’t tell what’s going on and who’s doing what to whom.”