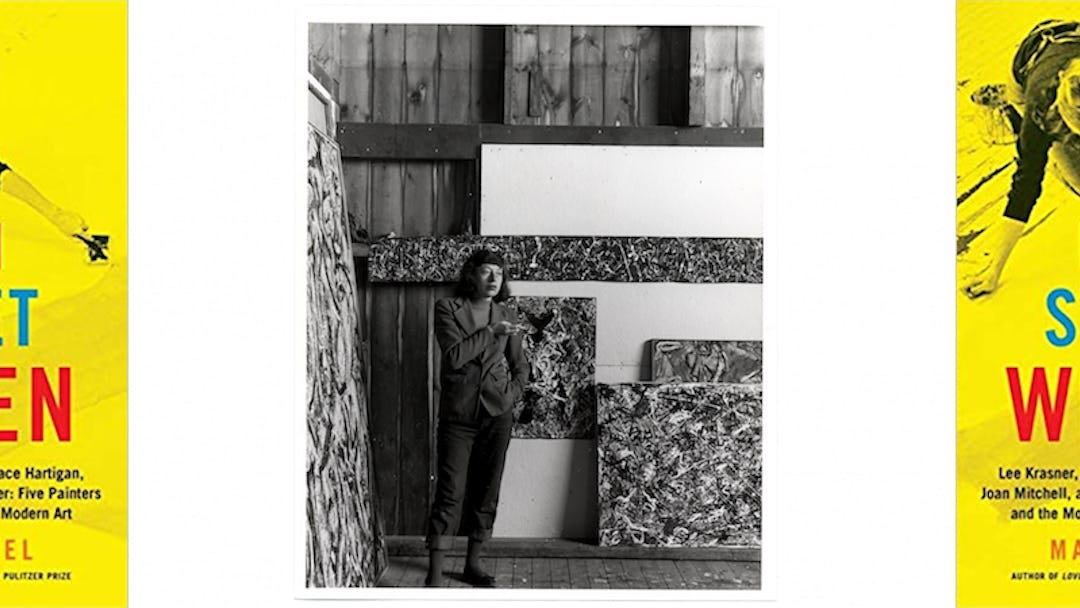

When we talk and read about mid-20th century abstract artists, the names mentioned are inevitably those of men. Now, Mary Gabriel is hoping to change that. In her hefty and engaging new book Ninth Street Women: Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, and Helen Frankenthaler: Five Painters and the Movement That Changed Modern Art (out now from Little, Brown), the Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award finalist (for Love and Capital: Karl and Jenny Marx and the Birth of a Revolution) Gabriel brings the burgeoning New York scene to vivid life, chronicling the lives of these five revolutionary women — “not as muses,” notes the book copy carefully, “but as artists.”

FROM CHAPTER 49, “A WOMAN’S DECISION”

The realization of my first strong desire to choose, to decide, to find, to move myself consciously in a chosen direction gave me for my whole life, as I now see it, a feeling of victory not over someone else but over myself, not bestowed from on high but personally acquired. — Nina Bererova

Back in the city in late July, Grace [Hartigan], Larry [Rivers], Mike Goldberg, Frank [O’Hara], Joe LeSueur, and Elaine [de Kooning] were sitting together as they often did at the Five Spot. “It was after hours,” Elaine said. “They weren’t serving any more drinks, and the band was just playing in a very desultory fashion, and everyone was kind of tired and winding down.” The smoke-stained walls of the bar above the wooden wainscoting were, by that time, plastered with notices about openings, poetry readings, plays, and performances. Those who wanted to talk sat away from the area designated for musicians (it couldn’t quite be called a stage). But those who wanted to be in the music sat at small tables a few feet from the pianist, who beginning that month was thirty-nine-year-old Thelonious Monk, accompanied by John Coltrane on the tenor sax. When the artists first began hanging around the bar, owners Joe and Iggy Termini had hired mostly white musicians who played like black jazzmen. Larry was one of them but thought it a shame that they should settle for second or third best when the greats were looking for jobs. Monk had lost his cabaret card allowing him to play in nightclubs because he had taken the rap on a drug charge to spare a friend a long prison sentence. “Through a very convoluted grapevine he heard that if he wanted it, he had a three-month gig right here in New York City,” Larry said. Monk accepted the offer.

A hip maestro in his cape and sunglasses, Monk performed for an appreciative audience comprised mostly of derelicts and artists. He played the way the artists painted. Each night when he walked in he knew what he wanted his music to do, but he had no idea what notes he would strike to achieve it or whether the men who played with him would be able to follow his lead. “I always had to be alert with Monk, because if you didn’t keep aware all the time of what was going on you’d suddenly feel as if you’d stepped into an empty elevator shaft,” Coltrane said. Sometimes, though, they both caught the music, and then Monk stopped playing and let Coltrane carry it alone while his large body danced, transported. The artists who listened sat mesmerized. No one had heard such music before and might never again. They witnessed at once its birth and its death. Unlike their paintings, when Monk’s miraculous music stopped it was gone forever. It was not written down, it had not been recorded, it existed like cool air filling the hot night and sweetening their memories.

Soon word spread through the 52nd Street jazz community about a new dive downtown. Men who would be legends began showing up to play. Cecil Taylor was among the first, then Charles Mingus, Miles Davis, and later Ornette Coleman, who described his music as “something like the paintings of Jackson Pollock.” Not only the performers, but also the audience became more racially mixed at a time when racial tensions in just about every other part of the country were at the boiling point. The Five Spot became a creative and social sanctuary, protected by its decrepitude from the meddling world beyond.

In the wee hours of that July morning in 1957 when Elaine and Grace and the gang were seated in their regular corner of the half-empty bar, a thirty-year-old musician named Mal Waldron arrived with a singer he had recently begun accompanying on the piano. “What I do remember, very distinctly, was the excitement that ran through the place when word got around that Billie Holiday had just come in,” Joe LeSueur said. “The table where she sat with Mal Waldron wasn’t far from ours.” There were few people living whom the artists in that bar respected more than Billie Holiday. In fact, Joan, Mike, and Frank had stayed up until three a.m. that June to hear her sing at a nearby movie theater. Billie embodied the artists’ struggle. She had paid the price for her gift from the time she was a child, burdened by the fact that she was not only a woman, but a black woman. At forty-two, after a lifetime of hard work, bad men, worse drugs, and cruel discrimination, her health and her finances were poor, but she had retained her dignity. Lady Day stood majestic. Tall, slim, her hair pulled back tight from her face, her eyes large and weary, it seemed as if pain had only made her more beautiful.

Frank, who had once called Billie “better than Picasso,” had gotten up to use the men’s room by the musicians’ platform and then stopped just outside the door. Mal Waldron was at the piano. “Suddenly we heard this voice whispering,” Elaine said. “It was Billie Holiday, you know, after she had been told she couldn’t sing anymore. And she was just whispering a song.”The session that none of them would forget, and many others claimed to have witnessed, continued until morning when the rising sun painted a line of blue along the horizon. They had barely dared to breathe during those sublime moments while Billie sang and Mal played. Everyone felt it. The kid from East Harlem who was allowed to listen from the phone booth because he was too young to sit in the bar. The painters and poets and writers and musicians who sat shoulder to shoulder, knee to knee around small tables crowded with empty beer pitchers and overflowing ashtrays. The drunks for whom life held little that could qualify as beauty. Hearing her gave them all courage; by dawn their faith was restored.

Ninth Street Women: Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, and Helen Frankenthaler: Five Painters and the Movement That Changed Modern Art is out now.