The New York Film Festival has run longer than most of his prestigious contemporaries — the 56th annual edition ended yesterday — and though it’s easy to lump them all together, it’s really an altogether different kind of festival. It stretches out for a longer period, three weekends and two weeks, as opposed to the two weekends plus one week and change standard of Sundance, TIFF, and SXSW — but it shows fewer movies than those festivals, presenting its patrons with a carefully selected and delicately spaced menu, instead of an all-you-can-eat buffet. It’s actually possible to see most or even all of the movies that play at the NYFF, and one year, your correspondent may do just that. This was not that year. But, to supplement my top-of-the-fest recommendations, here are a few more NYFF faves that will hopefully make their way to you soon(ish).

The Favourite

“They sh*t in the streets ‘round here,” the servant explains. “’Political commentary,’ they call it.” The line comes so early in Yorgos Lanthimos’s latest that it’s easy to see the wink — that he’s fully aware of the pitfalls of obviousness and clumsiness that await anyone attempting political commentary at this particular moment, but he pulls it off in scene after scene of this deliciously nasty comedy/drama, in which two ruthless women (Emma Stone and Rachel Weisz) vie for the affections of Queen Anne (Olivia Colman), and the proximity to power that entails. The drawing-room wit and period setting are atypical for Lanthimos, though he handles both with ease — and sooner or later, his trademark narrative brutality and visual uneasiness come out to play as well. Yet it never seems desperate to shock, the way even his best films have tended to; this is a story of power and subjugation, a point driven home by its potent closing images.

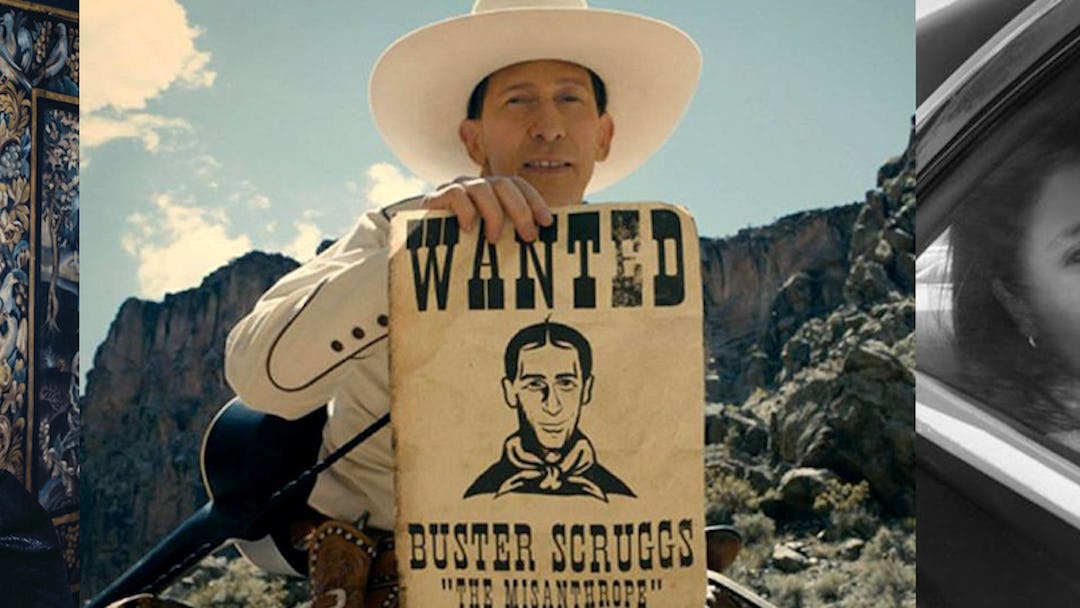

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs

Joel and Ethan Coen tell six stories — “Tales of the American Frontier,” according to the on-screen subtitle — in a land, as the title character puts it, “where the distances are great, and the scenery monotonous.” The results could’ve been scattershot, veering as it does between slapstick comedy, straight-up fantasy, existential darkness, and genuine warmth. Yet the stories are bound by the Coens’ irresistibly florid dialogue (a touchstone particularly appropriate to the genre, as evidenced by this film and True Grit before it) and by their often-underestimated (or altogether ignored) affection for their fellow man. Terrific performances abound, with particularly high marks to Zoe Kazan as a worried woman of the West and Stephen Root as a chatty bank teller who is not to be underestimated.

Roma

Alfonso Cuarón’s latest does so many things at once, none at the expense of the other, that it’s kind of a miracle. Set in Mexico in the early 1970s — and influenced by his own childhood memories — it’s an Y Tu Mamá También-style examination of the country’s class and political struggles as seen through a distinctively personal lens, the intermingled stories of two women abandoned by irresponsible men and rising to the occasion. As ever, the patience and control of the filmmaking is astonishing, and his signature long takes are more felt than seen; they don’t call attention to themselves anymore, and don’t need to. The takeaway is not visual pyrotechnics, but emotion; the empathy and humanity of his work, always present, is this time downright overwhelming.

At Eternity’s Gate

“When facing a flat landscape, I see eternity,” Vincent Van Gogh asks. “Am I the only one who sees it?” Julian Schnabel asks that question (over-asks it a bit, to be quite honest) in this biographical drama, which covers the last few years of Van Gogh’s life — a period in which he felt like a rudderless failure, and went a bit mad. Gate respects and honors the man, played with full-blooded power by Willem Dafoe, but isn’t afraid to puncture him occasionally (often via his interactions with an entertaining Oscar Isaac, as friend/rival Paul Gauguin). This is an ideal match of director and subject; many of these compositions are, yes, painterly, but Schnabel also brings a technician’s understanding of the art and a fellow journeyman’s sympathy, using intensely personal handheld camerawork to capture the artist’s inner life, and not just the immortal work he created.

Shoplifters

Hirokazu Koreeda’s Palme d’Or winner is a fascinating exercise in the power of perspective in regarding protagonists, though it’s nowhere as dry as that sentence makes it sound. (Put that quote on the poster, Magnolia!) It’s the story of a family bound by desperation, scraping by on bits of work and stolen food, and how they take on a new member who seems in even direr straights. “I bet they’re relieved she’s gone,” the mother says of the little girl from the abusive home, and it feels less like a kidnapping than just another shoplifting. Koreeda works in such a deliberately slice-of-life style, with such assumed sympathy for its protagonists, that the contrast when suddenly seeing this story from the outside is overwhelming; it’s the kind of movie that you don’t realize has snuck up on you until you’ve already been clobbered.

Divide and Conquer: The Story of Roger Ailes

Roger Ailes was a sexual harasser, a propagandist, a bully, and arguably the most important, influential media and political figure of the 21st century. Director Alexis Bloom’s biographical documentary traces the Fox News head’s ascendance from the quintessential ‘50s suburban upbringing to show business to politics to back again, meticulously tracing how he brought the techniques and lessons of one to the other, in order to create a toxic platform that weaponized the fear and paranoia that was such a key component of his personality. It’s a hell of a story, expertly crafted, but more importantly, Bloom gives voice to several of his accusers, listening to and believing them. It becomes, very explicitly, a movie about coming forward — and the small sliver of satisfaction, at long last, for those who did.

(NYFF)

The Times of Bill Cunningham

Bill Cunningham was a New York institution, a Times fashion photographer who pedaled around town on a bicycle, wearing his unmistakable blue jacket and toting a simple old camera, taking snaps of Gothamites out and about for his Sunday spreads. His story was told in the very good 2010 documentary Bill Cunningham New York; this one plays best as a compliment to that one, with director Mark Bozek using a lengthy 1994 interview with Cunningham as his framework. As such, it meanders a bit, sometimes feeling too chained to that interview, and Bozek makes a few other dodgy choices (particularly musically). But the film is lifted by Cunningham’s considerable warmth and good cheer — and given poignancy by his fragility, his ability to get emotional quickly and fully. Most of all, it’s powered by his clear and genuine love for the city. “I can’t wait to go out in the morning,” he insists, and you believe him. “I don’t think of it as work. I enjoy myself!”