Modern online media is all about the signal boost, so every Friday here at Flavorwire, we take a moment to spotlight some of the best stuff we’ve read online this week. Today, an oral history of Britney’s breakthrough, deep dives into the shifting landscapes of streaming TV and children’s online entertainment, and an eye-opening look at how the industry has shifted in the year of #MeToo.

The New York Times on who replaced the #MeToo-ed men.

It’s been a year since the Times and the New Yorker dropped their bombshell reports of years of sexual harassment and assault by entertainment mogul Harvey Weinstein, beginning a powerful movement to call out such figures in the industry, and hold them accountable. Surveying the fallout of that year, the gender and interactive teams at the Times made a starling discovery: nearly half of those who replaced them in those powerful posts were women.

The analysis shows that the #MeToo movement shook, and is still shaking, power structures in society’s most visible sectors. The Times gathered cases of prominent people who lost their main jobs, significant leadership positions or major contracts, and whose ousters were publicly covered in news reports. Forty-three percent of their replacements were women. Of those, one-third are in news media, one-quarter in government, and one-fifth in entertainment and the arts. For example, Robin Wright replaced Kevin Spacey as lead actor on “House of Cards,” Emily Nemens replaced Lorin Stein as editor of “The Paris Review,” and Tina Smith replaced Al Franken as a senator from Minnesota.

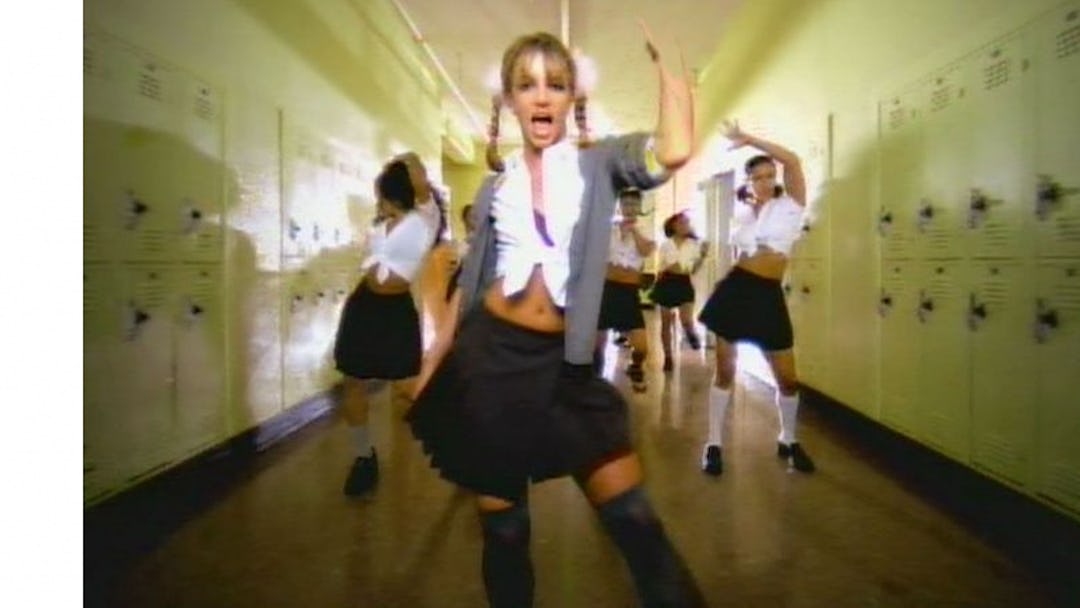

The oral history of “…Baby One More Time.”

Britney Spears’ earth-shattering debut single was released 20 years ago this week (feel old, etc.), so Entertainment Weekly‘s Jessica M. Goldstein tracked down several informed voices — including Jive Records president Barry Weiss, music historian John Seabrook, and Nigel Dick, director of the song’s iconic music video — for the low-down on how it went down.

Nigel Dick: She said, “I want to be in a school with a bunch of cute boys and do some dancing.” Barry Weiss: Her idea was the whole Grease thing, dancing in the hallway. She gave the kernel of the idea to Nigel, and he came up with the rest. Nigel Dick: Your initial reaction to this is, I’m being told by a 16-year-old-girl what I should do… [But] this girl is 16 and I’m a grown man; perhaps she has a better perspective on her audience than I do. So I swallowed my pride. John Seabrook: Britney knew better than the adults what people wanted and I think that’s also significant, because I think the adults began to realize that they didn’t necessarily know what the kids wanted anymore.

Alexis C. Madrigal on Toddler YouTube.

There was a dark period on our household when my daughter became obsessed with bizarre YouTube videos from a content creator called “ChuChu TV,” and even thinking of the cheerful incantation of that name, at the beginning of each video, still sends chills up my spine. The Atlantic‘s Alexis C. Madrigal decided to find out more, investigating the origin story of this wildly successful animation company, visiting their studios, and analyzing what the success of ChuChu and companies like it means for the future of children’s entertainment.

The new children’s media look nothing like what we adults would have expected. They are exuberant, cheap, weird, and multicultural. YouTube’s content for young kids — what I think of as Toddler YouTube — is a mishmash, a bricolage, a trash fire, an explosion of creativity. It’s a largely unregulated, data-driven grab for toddlers’ attention, and, as we’ve seen with the rest of social media, its ramifications may be deeper and wider than you’d initially think. With two small kids in my own house, I haven’t been navigating this new world as a theoretical challenge. My youngest, who is 2, can rarely sustain her attention to watch the Netflix shows we put on for my 5-year-old son. But when I showed her a ChuChu video, just to see how she’d react, I practically had to wrestle my phone away from her. What was this stuff? Why did it have the effect it did? To find out, I had to go to Chennai.

Nicole LaPorte on Hollywood’s middle-class struggle.

Man, there is so much TV now, from so many deep-pocketed providers, everybody in the industry must just be making out like bandits, huh? Well, yes, if you’re an above-the-name star or creator; if you’re a worker bee, not so much. Fast Company‘s LaPorte takes a deep dive into how the shifts in the television landscape have found supporting players and writers, who would’ve made a comfortable living in comparable gigs during the network days, working for minimum wage and picking up part-time jobs:

Much as with the rest of U.S. industry, Hollywood’s middle class has seen the stability that reigned from the 1940s to the 1980s slowly chipped away in pieces over the last several decades. In 1993, the so-called fin-syn laws, which prevented companies from owning a production studio and a network, were abolished, ushering in an era of consolidation that reduced competition. Around the same time, cable television exploded, which diverted eyeballs and advertisers from the Big Four networks, which had been the most reliable providers of job security and good pay. In addition, most original programming on cable networks was produced on the cheap. In 2007, a Writers Guild strike, just as the global economic collapse began, led to a contraction from which workers have not fully recovered. Networks slashed their budgets for lucrative overall development deals for writers who were in any way associated with hit shows, and salaries were slow to return to pre-downturn levels. Then came the arrival of streaming, which has only accelerated the decline for workers. A Netflix innovation, such as releasing all episodes of a season all at once to encourage binge watching, has been good for viewers, but it’s spurred an industry-wide shift to drastically shorter seasons, from the traditional 22 episodes of broadcast networks to as few as 10 or even eight or six, which means landing a TV gig is no longer necessarily even a full year’s work. The tech entrants into Hollywood typically do not sell their shows to other platforms, which means there are no syndicated reruns, and networks, feeling the pressure to keep up, air far fewer reruns. Together, these developments have largely ended the residuals system. Hollywood operated on the principles of the gig economy well before it became fashionable, and talent has relied on those supplemental payments as a potential cushion in between jobs.