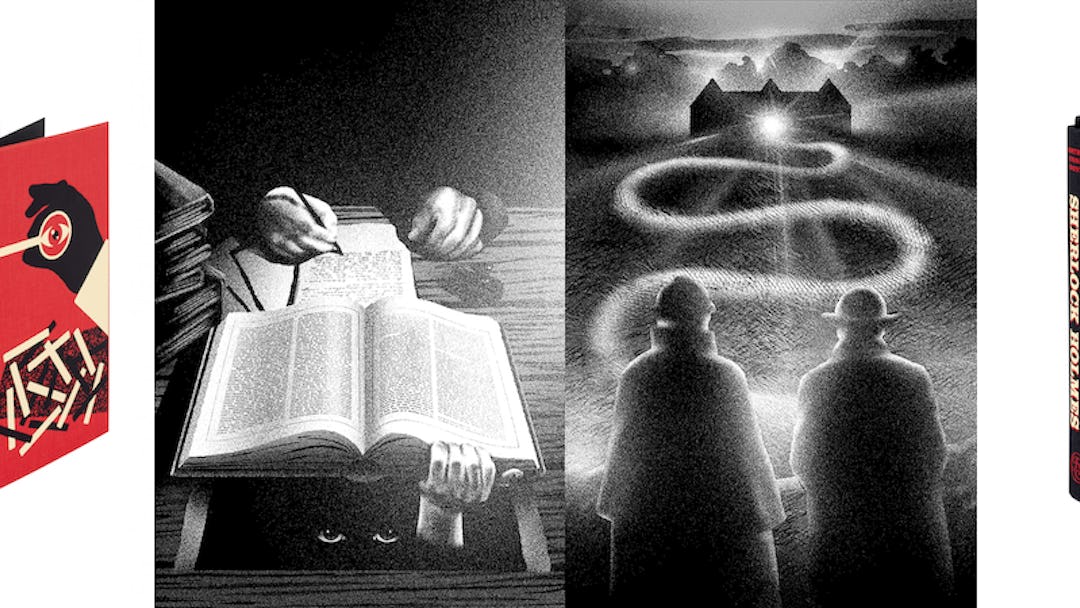

We’ve brought you a fair amount of proof that Folio Society is one of the best gift book publishers in the business, thanks to their handsome new editions of literary classics, beautifully bound and illustrated with new art. But their presentation isn’t just cosmetic; their exclusive introductions offer insightful context, analysis, and criticism. Take, for example, Pulitzer Prize-winner Michael Dirda’s new introduction to their Selected Adventures and Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes (out now), which collects 10 of the immortal detective’s best cases from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes and The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes; we were lucky enough to get our hands on an excerpt from Dirda’s introduction, which we’re happy to share here.

FROM THE INTRODUCTION TO ‘THE SELECTED MEMOIRS AND ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES’

Poll any group of devotees to name Holmes’s greatest cases, setting aside those recorded in the novels, and the top choice would almost certainly fall on ‘The Speckled Band’, which was also Conan Doyle’s own favorite. Close runners-up would include ‘A Scandal in Bohemia’, ‘The Red-Headed League’ and ‘Silver Blaze’. All these are here, plus six others, most notably ‘The Greek Interpreter’, which introduces Sherlock’s smarter but sedentary older brother Mycroft, and ‘The Final Problem’, wherein the great detective confronts the Napoleon of Crime, Professor James Moriarty. Each and every one of these stories offers its own distinctive pleasures.

But just what are those pleasures? Shortly after he’d been sent two or three of these tales, Herbert Greenhough Smith – the editor of The Strand Magazine – announced that he had discovered ‘the greatest natural-born storyteller of the age’. That word, ‘natural-born’, is particularly appropriate since Conan Doyle could compose a Sherlock Holmes adventure in a week or less, with hardly any need for revision. Once he had worked out his plot, the writing simply flowed . . .

Early on Conan Doyle also learned to charm – or do I mean torment? – readers by referring to Holmes’s many unrecorded cases. Just in these ten stories the detective or Watson mentions, without comment, the Trepoff murder, Ricoletti of the club foot and his abominable wife, the singular tragedy of the Atkinson brothers at Trincomalee, the affair of the aluminum crutch, and several others. The most famous of these cases ‘for which the world is not yet prepared’ is unquestionably that of ‘The Giant Rat of Sumatra’, but it is alluded to in one of the much later stories, ‘The Sussex Vampire’. No matter. Once you’ve read this Folio Society selection of Holmes’s shorter adventures, you’ll want to go on to all forty-six of the others, as well as to the more elaborate crimes unravelled in the four novels. As it happens, my own devotion to Holmes and Watson dates from the age of ten when I first opened that broodingly atmospheric Dartmoor tale of spectral horror, The Hound of the Baskervilles (1902). The last Holmes novel, The Valley of Fear (1914), richly shows off Conan Doyle’s imaginative range, as it involves an impossible-seeming cipher, the shadowy presence of Professor Moriarty, a genteel country-house murder, and a hard-boiled insider’s account of an American criminal organization.

Starting with Sidney Paget in The Strand, many artists have produced more or less compelling illustrations for these wonderful stories. To this number one must now add Max Löffler, whose subtle, trompe l’oeil artwork invites close attention, each of his enigmatic pictures revealing far more than initially meets the eye. As it happens, the very same might be said of Watson’s accounts of Holmes’s cases – in spite of their smoothness and polish, they bristle with textual mysteries, lacunae and anomalies, evidence that the good doctor was, at the very least, a poor proofreader. More importantly, these oversights and factual inconsistencies readily spur multiple conjectures from those who ‘play the game’ of pretending that the detective and his chronicler really existed. What, for instance, does it mean when Holmes refers to his landlady as Mrs Turner? Did something happen to Mrs Hudson? How is it that Watson can regularly leave his home and medical practice to go off gallivanting with his old friend Sherlock? Could the doctor’s marriage be unhappy, possibly on the rocks? At one point Mrs John H. Watson actually calls her husband ‘James’; might she have been daydreaming of a lover with that name, perhaps James Moriarty? Might she even be some other woman rather than the former Mary Morstan? For that matter, is Moriarty really anything more than just an aging mathematics teacher? Everything we know about him derives from Holmes who, given his drug habit and unstable personality, might have delusively imagined a criminal mastermind in his own image. Such questions can be, and are, endlessly probed, debated and rebutted. Sherlockians who ‘play the game’ quickly learn to seek the deeper implications hidden beneath Watson’s surface narrative. Need I add that virtually every woman client under the age of forty has been suspected of being a secret paramour of either Holmes or Watson?

Such enjoyable speculation, despite its apparent frivolity, hints at what keeps the Holmes stories so revered: their infinite re-readability. Upon first acquaintance, one delights in their plots, characters and startling deductions. These are, to begin with, first-rate detective stories. But when you return to them, as you will, it grows clear that they are also something more. Vincent Starrett, a founding father of Sherlockian scholarship, described the stories as adult fairy tales and compared Watson’s introductory phrases – ‘In glancing over my notes’ or ‘I had called upon my friend, Mr Sherlock Holmes’ – to variations on ‘Once upon a time’. In truth, the exploits of Sherlock Holmes and Dr Watson serve as portals to an enchanted realm, the romantic, half imaginary England of the 1880s and 90s; they are studies in coziness as well as scarlet. Whenever or wherever you begin one of them, a deep contentment quickly follows, as if you were settling into a soft easy chair, near a blazing fire, with something warming to drink close at hand. Outside the gaslights faintly glow, the hansom cabs trundle by. Suddenly, there’s a knock on the door, a visitor for Mr Holmes, and once again, the game is afoot.

By Michael Dirda, from “The Selected Adventures and Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes,” out now from Folio Society. All rights reserved.