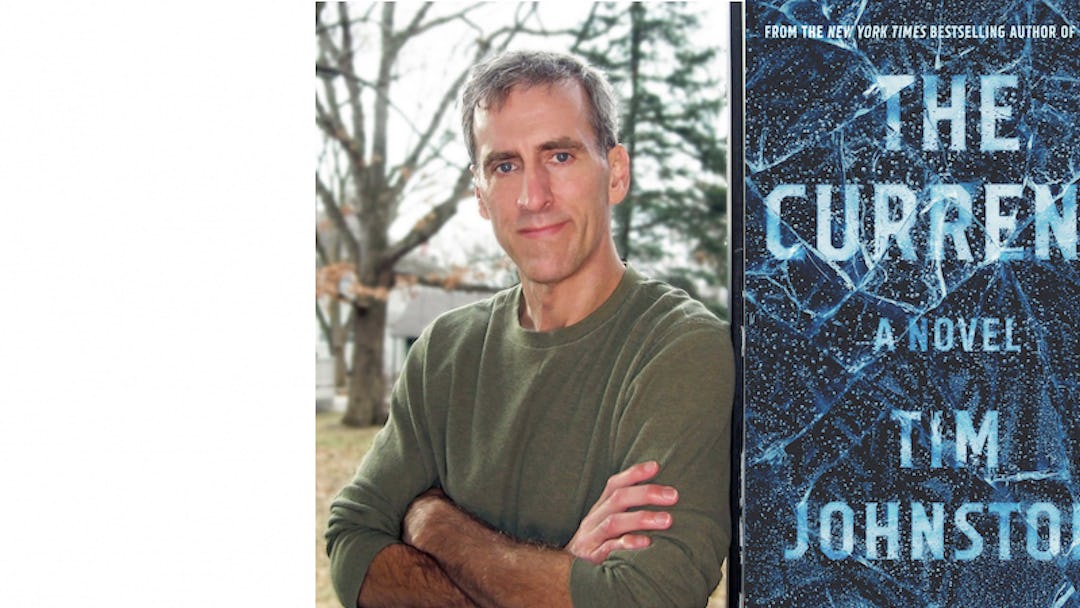

Tim Johnston’s debut novel, 2015’s Descent, was both a critical success and a New York Times bestseller — so anticipation is obviously high for his newest book, The Current (out this week from Algonquin Books), a story of loss, survival, and buried secrets. But the ambitious author is up for the challenge.

“The Current may differ from other ‘literary suspense/crime’ novels in that it does not always offer absolute certainty or resolution or justice; nor does it race toward an ultimate confrontation between protagonist and antagonist,” Johnston explains. “Instead it moves in and out of time, in and out of families, building on the wounds and obsessions of characters who, while not villains themselves, do not always act nobly or even legally. The individual currents of characters barely known to each other combine through chance and history into a single current of loss, but also love.”

We’re pleased to present this excerpt from the book’s opening chapter.

FROM CHAPTER ONE OF ‘THE CURRENT’

THE TWO GIRLS, young women, met for the first time the day they moved in together, first semester of that first year of college, third floor of Banks Hall, a north-facing room that overlooked green lawns and treetops and streams of students coming and going on the walkways below. Roommates by mysterious processes, perhaps a computer algorithm, perhaps a tired administrator plowing his way through a thousand folders, the girls cried at first to become friends, then tried simply to get along, and finally put in for reassignment, each without celling the other, and by the end of the winter holidays had both moved into new rooms with new roommates. If they saw each other on campus after that, they pretended they hadn’t; they looked away, they looked at the sky, they received phone alerts of highest importance. They seemed to have made a pact of mutual invisibility, and chis pact might have gone on forever, all the way through college at least, if not for a literature class in the fall of their sophomore year. The class – The Romantics, it was called, like the band – was crammed into a too-small classroom, a space not much bigger than chose dorm rooms, and yet neither girl wanted to be the one to drop, but instead kept coming to class and caking her seat. Three weeks into the semester one of the girls, arriving lace, had no choice but to sit next to the other, and from then on they made a point of it: sitting shoulder to shoulder, nearly, in the crowded classroom, eyes on the profes sor, notebooks open . . . a game of academic chicken that neither girl felt too great about, to be honest, but felt even less great about losing, and so on it went. Until, one day, one of the girls-the one named Caroline-turned to the other girl, whose name was Audrey, and asked to borrow a pen, setting off a backpack search of such intensity that the professor herself, prowling her narrow crack of floor at the head of the class, halted, one eyebrow cocked, while the girl hunted, and dug, and at last fetched up from the very last place it could have been a plain blue Bic with bite marks on the cap. The pen passed from hand to hand, and in this simple way the girls started over. Their story reset itself, and they became friends. ON FEBRUARY 4 of that same school year, Caroline Price turns twenty, and two days later at the Common Grounds Cafe her friend Audrey Sutter is telling her that her father is sick, and she needs to get home and she doesn’t have a car, and the Visa her father gave her is maxed out on tuition, and so she’s wondering, what she wanted to ask is, could she possibly borrow $150 for bus fare, she can pay Caroline back when … well, as soon as she can? And Caroline Price, sipping black coffee, shudders at some inner picture-perhaps the interior of that bus: God-knows-how-many miles up to the Arctic to see your sick – your dying? – father and nothing to keep you company but the smell of diesel and the cold, droning miles and probably some mullet-headed yahoo with halitosis just waiting for you to take those headphones off, like you would ever take them off! It’s not the Arctic, Audrey could remind her, it’s Minnesota, but to a Georgia girl like Caroline it might as well be. Even Memphis, less than a three-hour ride north from her hometown, is too much. An ice storm last week, a tree limb snapping the power line behind her apartment, and all weekend in Troy’s dorm room with its stink of boys, or in the library, or right here in the cafe, before the city got the power line repaired … Audrey sitting meanwhile across the cable, holding Caroline’s image in her wet blue eyes-chose pale, Arctic eyes-waiting, until at last Caroline says, Sure, of course, what time does your bus leave, I’ll drive you to the station, and like that the storm lifts from Audrey’s face, and wiping the tears from her cheeks she says, like one who has just regained her senses after a blow to the head: “Caroline, you look so nice today. What’s going on?” Because, as Caroline herself would be the first to admit, unless she’s off to see Troy on a Friday night, or unless she’s going out dancing with her volleyball girls, she tends to look like what she is: a sweats-and-sneakers kind of girl, a big, loose athlete, on her way to or from practice. But when she decides to look good? When she hits the shoes and skirts and makeup? It’s like she swooped down from some other world, a sudden alter-Caroline of extreme beauty and dazzle. But it’s nine o’clock on a Tuesday morning and Caroline is on her way to class, so – what gives? A good question, a fair question, but Caroline must fly – running late again, always running late, Audrey watching through the glass as her friend fast-walks toward campus in her short jacket and short skirt and her tights, leaning into a cold headwind that seems to push at her with actual purpose, as if to discourage her, stop her even, turn her back – Go back to your room, Caroline Price, go back to your bed, curl up under the heavy quilt the old women of home sewed just for you, no warmth like that in the world, not even a boy’s . . . Caroline’s boot heels clock-clocking on the sidewalk, her long fingers stuffed as far as they’ll go into the fake pockets of her jacket, batting tears from her chickened lashes and asking herself too, perhaps, what’s going on. A meeting with a professor, that’s all. After class, if she has time, said the email. So, OK. Lose the Adidas and the hoodie for a change, but that’s it, effortwise. It’s not anything sexual, this looking nice – she has a boyfriend, after all. And the professor is old – like, forties-old. But there are girls she knows who want that A so badly, who learned in middle school – hell, grammar school – how these things worked. The world. Power. But that power is a false power, girl, says her memaw. With her dentures and her bent little body. That power will turn on you like a stray dog. And the profs themselves, these older men, these wise and fatherly teachers; you could always tell who they had their eye on. And you watched it progress over the semester, the favored girl bringing it for a 9 a.m. class: the cloches, the hair, the earrings, the lashes. But that’s not what this is. Caroline would wear a damn Snuggie to class if she felt like it, and she would earn her grade according to her performance, just as she’d earn a win on the volleyball court where there are no grades and no flirting, only muscle and sweat and the unambiguous counting of points. As for the perfume, well, a girl wanted to smell nice when she looked nice. Just a touch, a fingerprint, on the neck. That was for you and not for anyone else. Certainly not for some forty-year-old man who wanted to see you after class, if you had time. But it was the good stuff, Audrey knew, having caught its scent over the smell of coffee even before her friend sat down: the little French bottle Caroline bought on her trip to New York City last summer, and the scent of which Audrey now associates with Caroline almost as intensely as the potent green slime she’d rub into her legs before practice and before each game and sometimes, in those old dorm room days, before going to bed. And it’s this weird remix of seems French perfume and overpowering muscle gel – that Audrey smells as she, too, leaves the cafe, stepping into that same cold wind but the wind pushing at her back as she moves in the opposite direction of Caroline – a wind not to stop her but to hurry her along home, the sooner to pack, the sooner to be ready when Caroline comes to get her, the sooner (though she knows this is not logical) to get home to her father, who of course has told her not to come, to stay in school, nothing to see here, says he, just a little touch of the inoperable cancer is all, nothing that won’t keep until you come home in the spring . . . And with such thoughts fluttering within her it seems actually a piece of these thoughts, like an escaped fragment, when the air itself bursts into violence just above her head – a sudden flurry and a kind of shriek as a bird nearly crash lands on her head, close enough to fan her with wingbeat, low enough to sweep something soft and alive along the part line of her hair; it’s the plush tail of a squirrel, she just sees, a juvenile, who rides like a pilot in the bird’s claws, this bird and rodent combo descending with flaps and cries to earth behind a low wall of hedges, a troubled landing that no one – she looks: students plod ding head-down, locked into phones, ear-stoppered – no one but her has seen or heard. And she steps around the hedges slowly, coming all the way around before she sees the bird – a hawk, sure enough – standing with its back to her, wings fanned out on the dirt like the wings of a broken craft, great riffling wings that become arms, crutches, here on earth, keeping the hawk upright atop the body of the squirrel; young, round-eyed squirrel, unsquirming in its cage of talons. The hawk rotates its head halfway round, puts two black eyes on Audrey and opens its sharp beak soundlessly. Audrey standing there doing nothing. Saying nothing, just watching. A passive but rapt witness to chis instance of wildness on a college campus. Predator and prey. The hawk watching her with those black eyes, that sharp beak, considering her – Audrey’s – intentions here, the pros and cons of waiting it out, until at last in a single high note the hawk says, You Little bitch, and lifts the great wings and unhooks the talons and with one windy beat is aloft again, and with another is gone. The young squirrel remains, wide-eyed, belly to the ground; in a state of rodent shock maybe. Or maybe it’s the dead-like stillness prey is said to adopt when all hope is lost, when it’s time simply to die. But then, suddenly, the squirrel leaps to its feet and flies into the hedges and there’s nothing where it had been, where the hawk had been, but a random patch of ground – and no one sees any of this but Audrey, and she will tell no one, not even Caroline; it’s her own personal event flown down from the sky- some kind of sign, surely, some kind of message: a last-second reprieve from death. And so enlivened – so incited – by this vision, she takes the four wooden porchsteps of the little gray rental house in two bounds, then likewise flies up the staircase that leads to the two upstairs bedrooms and begins tossing things onto her bed like one making her own escape. Like one whose own reprieve has just been assured.

Excerpted from “The Current” by Tim Johnston © 2019 by Tim Johnston. Reprinted by permission of Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. All rights reserved.