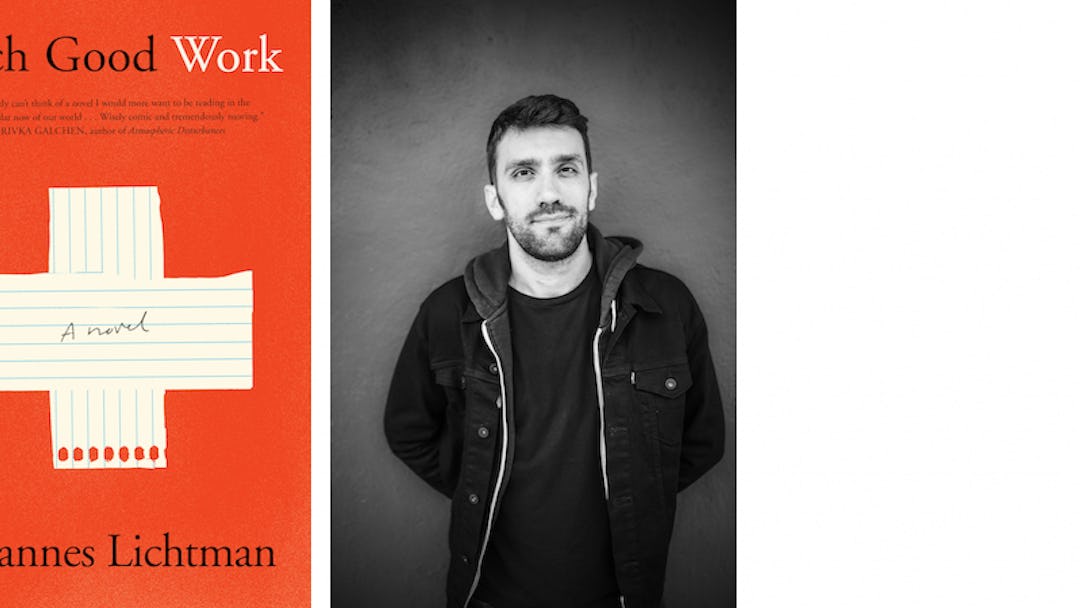

Is doing good even possible? That’s the provocative question posed by Such Good Work, Johannes Lichtman’s debut novel (out February 5 from Simon & Schuster). It tells the darkly comic story of Jonas, a newly sober teacher who decides to fully wipe his slate by taking a volunteer teaching job abroad. He finds himself educating young migrants at the peak of Europe’s refugee crisis, questioning not only his effectiveness, but his motives.

We’re pleased to present this excerpt from the book’s first chapter.

From “Wilmington, North Carolina – 2013” My students turned in drawings of animals with extraordinary life spans. I learned that there were species of tube worm that lived for up to one hundred and seventy years. Arctic whales more than two hundred years old. Clams with a life expectancy of four hundred. Sponges that had been alive for more than a millennium. A kind of jellyfish—the immortal jellyfish—that, after reaching sexual maturity, could revert to infancy again and again, maybe forever. “Really?” I said, holding up Lucy’s drawing. Lucy nodded proudly. She was a sophomore psych major. Her jellyfish wore a cape. A dialogue bubble above its head stated: I am immortal and a jellyfish. I hung Lucy’s picture on the whiteboard next to Ravi’s arctic whale, which had a horn and a side-profile smile. Ricky’s tube worm was a bright red plume with the caption The tube worm is a vagina-like creature that can grow to be up to six feet tall. It is a deep-sea invertebrate whose only predators are accidental ones—mainly large mammals trying to have sex with it. Kayla’s drawing was not a drawing but rather a full page of double-spaced text explaining why there shouldn’t be drawing assignments in a college creative-writing class. (Drawing animals is not creative writing any more than pottery is accounting.) She sat in the front row and glared at me. She had the posture of someone who spent her childhood balancing books on her head. She was almost certainly the treasurer of a sorority. I hung her essay next to all the animal pictures. My department chair, Norman, invited me to his office. Norman was a squirrelly man who always appeared to be bracing for a punch. He was from a leafy college town in the Northeast and looked out of place in Wilmington, a waterfront tourist strip that happened to have a university. He had hired me the previous summer after a string of maternity and rehab leaves of absence had left the department in need of temporary faculty who could be trusted to stay childless and sober. I wasn’t sure why, out of the pack of graduating MFA teaching assistants, he had picked me, but maybe one of my professors had gotten the wrong idea about me and put in a good word. “Look, Jonas, I’m not trying to be the administrator here,” Norman said. “But a student complained.” This student had felt uncomfortable with last week’s homework assignment: attend a stranger’s funeral. “Frankly,” Norman said, “I don’t know if I can blame her.” This student was Kayla. Norman waited for me to say something, but my mind was too foggy to find a good explanation. “No more funerals,” I agreed. Back in my office, I typed up a more traditional assignment: Write a story. My mind was always foggy lately. At age twenty-seven, it was my first semester sober, and without four doses of oxycodone a day, a couple tramadol in the mornings, a few methadone now and then, and a weekend bump of heroin to take the edge off, I’d been having trouble finding my words. Sometimes when I was standing in front of the class and one of the kids asked a good question, my brain would start firing off ideas, and it was like I was alive again. I’d explain the relationship between dialogue and narration in fiction, do an impromptu performance of how a scene from a popular movie would sound if a narrator were commenting on each piece of dialogue, and feeling my energy rising with the sound of their laughter, I’d circle back to answer the original question by describing the moment in their assigned reading when . . . when . . . when . . . but the words would scurry into the fog again and I’d be left um-ing and uh-ing like an idiot. Monday morning the students slumped through the door. They’d spent almost every Monday since they were five years old in a room like this. It took its toll—so often being somewhere other than where you wanted to be. When I used to get high, places were interchangeable. Everywhere was the best place ever—and then the worst. But now place mattered very much. There were few places I liked more than this classroom, with the cheap blinds over the windows, the long fluorescent light tubes overhead, and the students who, even though I often told them what to do, didn’t seem to hate me. Except for Kayla. Her dislike troubled me. I stood at the front of the class. I was wearing jeans and a navy cardigan that had been a gift from my ex. I had been growing my hair long since a methadone nightmare the year before had given me a fear of balding. The hair now reached down past my ears. It was strong and brown and shiny and probably the best thing I had going for me. I held up a stack of student stories. “This was concerning.” I paused. “You killed all your protagonists.” The students laughed nervously. Kayla maintained eye contact from her spot in the front row. “I’ll admit that this may be my fault. I probably shouldn’t have sent you to the funeral. That’s on me. I was trying something new.” I paused. “But here’s the thing: Life is long and usually ends in death. Stories are short and usually don’t. Characters can have problems without having cancer, and suicide doesn’t always have to be the solution.” I looked out at the students, hoping to see a reaction, which was a stupid thing to do, since, even when the students were in the middle of life-changing moments—when they realized that all experience was subjective or that they didn’t have to major in business administration—they almost never visibly reacted. But today, seeing no reaction, I panicked. I took a sip of water and gathered myself. “Please stop killing your characters. It’s bumming me out.”

Excerpted from “Such Good Work” by Johannes Lichtman. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster. All rights reserved.