Modern online media is all about the signal boost, so every Friday here at Flavorwire, we take a moment to spotlight some of the best stuff we’ve read online this week. Today, a complicated interview with a Hollywood legend, an examination of how a 20th century video game influenced 21st century living, and explosive commentaries on a cable news network and magazine cover story.

Jessica Roy on the “Sim City” effect.

For a lot of us, Sim City was a pleasant time-waster, a video game that was a little addictive and a lot of fun. But for a generation of urban planners, it wasn’t just recreation — it was an initiation. At The Lost Angeles Times, Roy interviewed more than a dozen city planners about how the game influenced their career path.

He spent many hours trying to build a city with no space for driving at all — only buses and trains. But like in real life, mass transit is expensive to build and maintain in “SimCity,” and some of the residents still want to drive, no matter how convenient your rail system is. He was never able to make it work. (Today, he’s a self-described “rabble rouser” working to halt a proposed freeway expansion.) That issue speaks to a larger criticism of “SimCity”: Wright’s vision imposed an old-school approach to city-building, influenced by Robert Moses and the Chicago school. For those early urban planners, and in “SimCity,” there were binary solutions to problems. To lower crime rates, build police stations. If people complain about traffic, build more roads. If you need space to build a freeway or a stadium, raze working-class neighborhoods. “A lot of the assumptions baked into that game are the normative assumptions that we need to be questioning,” Brown said.

Andrew Goldman interviews Peter Bogdanovich.

The Last Picture Show director’s massive Vulture Q&A is about as contradictory as the man himself: alternately insightful and infuriating, childishly petty and maturely mournful, conveying both what was exhilaratingly different about the New Hollywood movement, and the ways in which the men at its center replicated the worst behaviors of the Hollywood of old. (Of kissing his actresses, he explains, “It’s called getting to know your actors,” though there are no mentions of making out with John Ritter or Burt Reynolds.) Bogdanovich spills plenty of tea as well, perhaps most entertainingly (and dangerously) when describing his working relationship with Mask star Cher:

Tell me about your experience with her on Mask. Well, she didn’t trust anybody, particularly men. She doesn’t like men. That’s why she’s named Cher: She dropped her father’s name. Sarkisian, it is. She can’t act. She won Best Actress at Cannes because I shot her very well. And she can’t sustain a scene. She couldn’t do what Tatum [O’Neal] did in Paper Moon. She’d start off in the right direction, but she’d go off wrong somehow, very quickly. So I shot a lot of close-ups of her because she’s very good in close-ups. Her eyes have the sadness of the world. You get to know her, you find out it’s self-pity, but still, it translates well in movies… What did Cher think of you? Cher doesn’t like me. Why? Well, because I didn’t like her. She was always looking like someone was cheating her. I came to the set one day; I said, “You depress me, you’re always so down and acting like somebody’s stealing from you or something.” But finally, after about seven weeks of this, we started getting to like each other. She said, you know, we don’t watch out, we might end up liking each other. I said that would be amazing. And we did end up liking each other, and then when I sued the studio, she sided with the studio, of course. That was that.

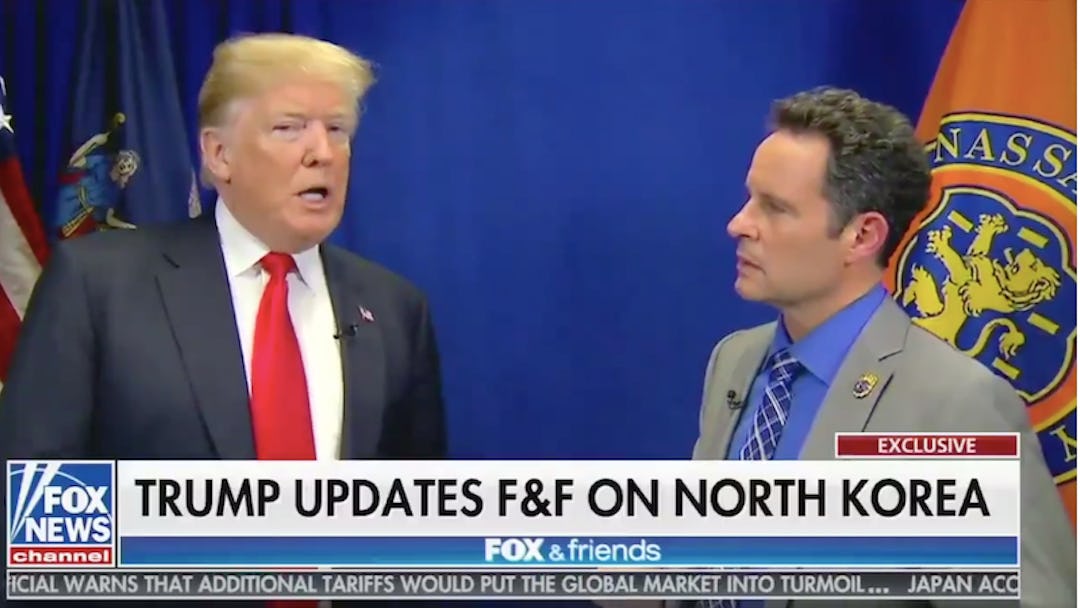

Jane Mayer on the Fox News White House.

Last week, we shared Molly Langmuir’s profile of Jane Mayer, in which the investigative reporter indicated she was working hard on a new blockbuster story. This week, it dropped: a penetrating, frankly terrifying look at how Fox News has morphed from a sophisticated engine for the dissemination of political talking points into, as one historian puts it, “the closest we’ve come to having state TV.”

Pete Hegseth, the Fox News host, and Lou Dobbs, the Fox Business host, have each been patched into Oval Office meetings, by speakerphone, to offer policy advice. Sean Hannity has told colleagues that he speaks to the President virtually every night, after his show ends, at 10 P.M. According to the Washington Post, White House advisers have taken to calling Hannity the Shadow Chief of Staff. A Republican political expert who has a paid contract with Fox News told me that Hannity has essentially become a “West Wing adviser,” attributing this development, in part, to the “utter breakdown of any normal decision-making in the White House.” The expert added, “The place has gone off the rails. There is no ordinary policy-development system.” As a result, he said, Fox’s on-air personalities “are filling the vacuum.” Axios recently reported that sixty per cent of Trump’s day is spent in unstructured “executive time,” much of it filled by television. Charlie Black, a longtime Republican lobbyist in Washington, whose former firm, Black, Manafort & Stone, advised Trump in the eighties and nineties, told me, “Trump gets up and watches ‘Fox & Friends’ and thinks these are his friends. He thinks anything on Fox is friendly. But the problem is he gets unvetted ideas.” Trump has told confidants that he has ranked the loyalty of many reporters, on a scale of 1 to 10. Bret Baier, Fox News’ chief political anchor, is a 6; Hannity a solid 10. Steve Doocy, the co-host of “Fox & Friends,” is so adoring that Trump gives him a 12.

Patrick Nathan on the danger of that Esquire cover story.

Esquire‘s March cover story, “The Life of an American Boy at 17,” prompted a bit of a firestorm online, and for good reason; its flat reading of white male heteronormativity, presenting the worldview of an annoyingly typical teenage bro as if it is some revelation in reportage, seemed tone-deaf and ill-timed to the cultural moment, and editor Jay Fielden’s insistence that his periodical was merely partaking of the good, old-fashioned, salon and dinner-table sport of debate did not sit well with Pacific Standard‘s Nathan:

What Esquire has done is not “engage in debate,” as Fielden claimed, but instead loudly shun concerns that queers, women, and people of color have raised for centuries, and that are especially pressing under the current presidential administration. Editorially, it has closed its eyes to reactionary whiteness and toxic masculinity, regurgitating unchallenged narratives that pretend these harmful ideologies are “neutral.” By refusing to connect the dots between ignorance and systemic violence, Esquire is actively policing who matters and who does not. It’s the same wound that pundits ripped open after the 2016 election, elevating and valorizing the suffering of white people, rather than focusing on the deadlier, more widespread pain of marginalized persons. What Esquire has upheld is the gentrification of American suffering, reiterating to its audience that pain and poverty and terror are irrelevant until they affect the white, the male, the straight, and the Christian. A common lament these days is our country’s alleged addiction to “identity politics,” as if the identities of marginalized persons are what’s corroding our political discourse. For me, though, identity isn’t about how I choose to approach politics, but about how politics has confined me. My queerness isn’t something I choose to think about every day; it is an identity assigned to me by an ignorance that threatens my life. It is ethical to demand, in return, that white people think of their own whiteness, that men see their masculinity as imposed from without.