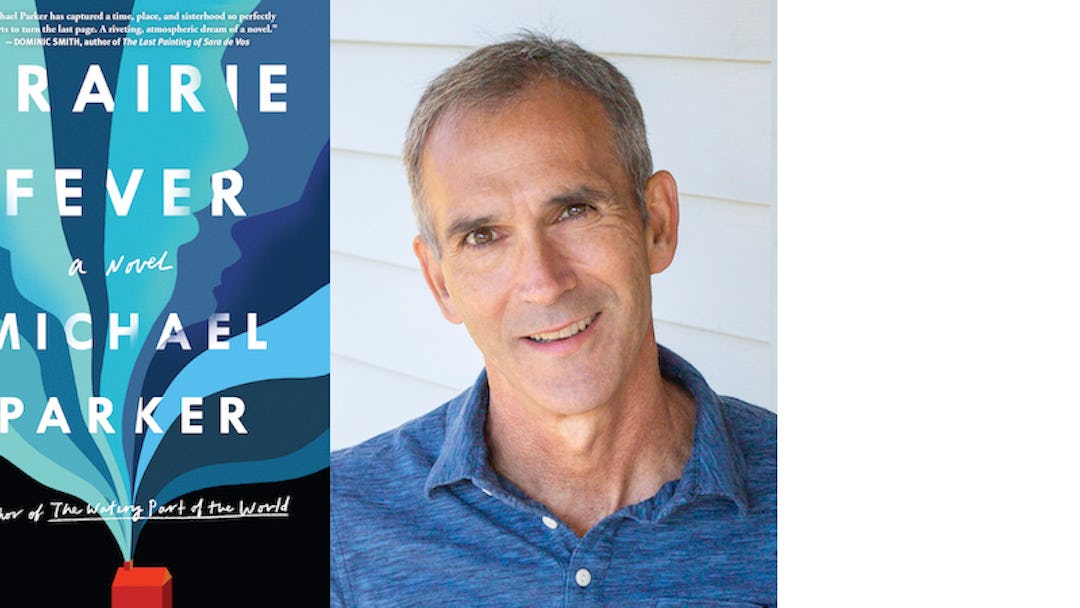

The Stewart sisters, Lorena and Elise, make their home in Lone Wolf, Oklahoma in the early 20th century, finding that in a rugged landscape and a tough world, the one thing they can count on is each other. Michael Parker tells their story in his new novel Prairie Fever (out this week from Algonquin Books), crafting the delicate tale of two sisters who have little in common – except for their place in the world. We’re pleased to present this excerpt from early in the book, detailing the convoluted process by which the sisters attend school, and establishing their strange but precious bond:

ELISE STEWART Lone Wolf, Oklahoma, January 1917 Winter mornings their mother kissed them both on the fore head, pinned the blanket around the two of them, and slapped the horse’s croup. Lorena held the reins. Elise wrapped her arms around her older sister’s waist and both girls shut their eyes against the icy wind of the prairie. On the way to school they recited items memorized from the pages of the Kiowa County News, with accompanying commentary. Elise: Alfred Vontungien left Lone Wolf to attend O.U. Norman. He is one of our most brightest and most promising young men. Good luck ro you, Alfred, in your studies. Lorena: Good luck, Alfred, outrunning the cow that licks your hair up ro five times a day. Elise: Burr Wells, who owns one of the best farms that ever a crow flew over, says he has a set of farmers this year who are farmers in fact. He can’t hardly get through praising his farmers. Lorena: It is a fact that farmers come in sets. Inside the blanket, they warmed themselves with words. The horse knew the way to the schoolhouse through the blinding snow. The teacher would be looking out for them. He would struggle into his coat and gloves and hat and come outside to unpin them. Off would fall the blanket, coated with ice crystals. Out would fall the words memorized from the newspaper. The teacher would shake the blanket , and the words from the newspaper would fall to the ground. The other words, not written, their words, along with their giggles, would float off into the snow. Lorena: While moving a cultivator plow last week near Gotebo, Eli Roberts was struck by the tongue of the machine, cutting an ugly gash under his chin and hurting him severely. The wound was dressed and he is getting along nicely. Roberts now has it in for everything with a long tongue. Elise: Edith Gotswegon of Lone Wolf has been placed at the top of the list of long-tongued things he has it out for. Lorena: In for, not out for. Elise: In or out for. Lorena: Chapman Huff had business in Oklahoma City. Elise: I bet he did, did Chapman Huff. Lorena laughed. Through the blanket, Elise saw her laughter leak out and lessen the menace of the wind. When the teacher, who was new that year, unpinned the blanket, Elise saw the comma separating the dids disappear in a puff of snow. “I bet he did did,” she whispered to Lorena, and the new schoolteacher whose name was Mr. McQueen, shook his head and said, “You two!” as he helped first Lorena and then Elise off the horse. On the first day they arrived by blanket, Mr. McQueen asked what their horse was called. They had been riding him to school every day for months, but now that Mr. McQueen had to unpin them he wanted to greet the horse by name. “His name is Sandy,” said Elise. Mr. McQueen looked distressed. Elise assumed it was because Sandy was the color of tar. “He would like to live by the sea. He does live by the sea, I mean. He gallops through the tidal pools.” “I see,” said Mr. McQueen, who seemed to have recovered. He introduced himself properly to Sandy and asked if he might accompany him to the shore. He had come from somewhere back east and Elise assumed he knew the ocean, but when asked during geography, he said he knew only rivers. He described crossing the Mississippi by train on his way west. He crossed at Vicksburg, where boys stood by the river in knickers stiff with mud. For a nickel, these boys would tie ropes around their waists and wade into the river and stick their hands into holes in the bank and pull out catfish. He told the story of a man named Charlie Carter who sat beside him for three states snoring drunk. Finally, in Arkansas, he woke up calling for his Beulah girl. All the boys and most of the girls thought this was hilarious, but Elise found it tragic. His Beulah girl having married another. Charlie Carter having drunk himself into a three-state slumber, so sick was he over the events that had befallen him. Oh Beulah girl, cried Charlie Carter. Elise sat in the middle of the classroom, studying Mr. McQueen. With her most woeful expression she implored him to understand Charlie Carter’s predicament. Have you nothing in your body but funny bone? Mr. McQueen caught her staring. He returned her stare as he talked of the Natchez Trace, which he claimed to be a path of prehistoric animals before Indians found it and then white men. He talked on a bit and then he called on her. “Reverend Womack closed the meeting at Bethel Sunday early due to heavy rains,” said Elise, quoting the Kiowa County News. Elise felt her sister’s tickling giggle, as if they were still tented atop Sandy. She looked outside. The wind had blown open the door to the storm cellar. Edith Gotswegon stuck out her too-long tongue. Eli Roberts had it in for her and out for her. Oh he did, did he? “Beg pardon?” said Mr. McQueen. The class was silent. They knew her to sometimes answer questions with quotes from the newspaper. She did it to them and to the teachers and to her piano instructor. Her classmates stared at their teacher. They were blind to commas adrift among the ice crystals, and their stony hearts were immune to Charlie Carter’s loss of his Beulah girl. She looked outside again, but the snow was too thick to see the storm cellar. Sandy galloped along the edge of the surf. Waves lapped at his hooves. He smiled, tickled. She smiled, tickled. A pelican lit on Sandy, the very spot where Elise had sat clutching her sister the four frigid miles to school. “Among the interesting relics owned by Captain James Lowery, of Missouri, currently visiting his son in Lone Wolf, is a stout old-fashioned hickory walking cane,” said Elise. “The stick was cut and used for some time by Henry Clay, coming from the Clay home in Kentucky.” “Elise,” whispered Lorena. “That is a long way for a cane to travel. It must be very stout,” said Mr. McQueen, who did not call on her again that day.

Excerpted from “Prairie Fever” by Michael Parker, out now from Algonquin Books. Used by permission.