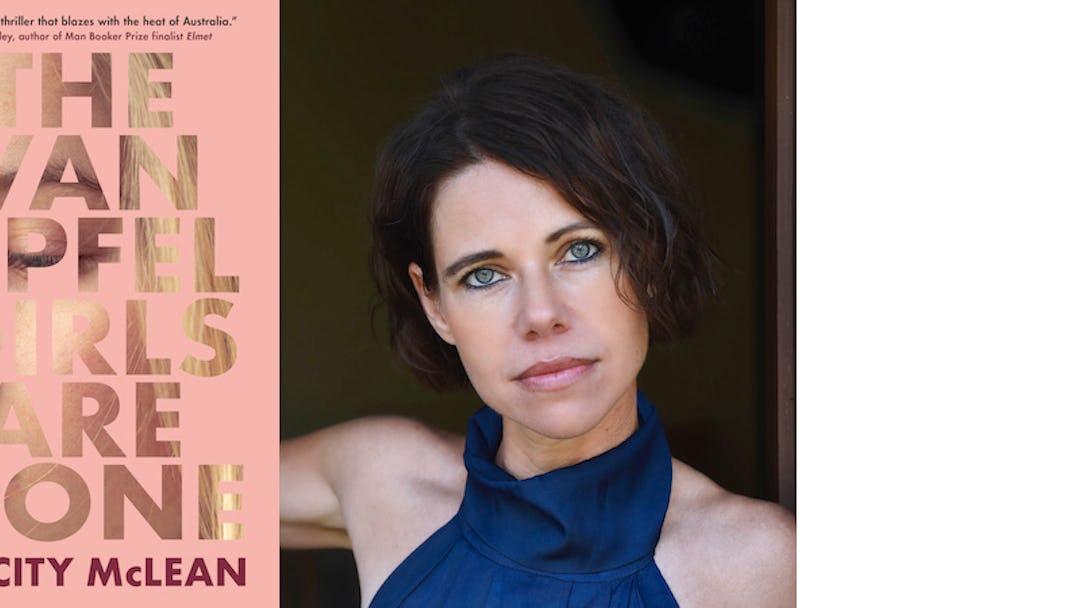

Thanks to The Player, it’s easy to be skeptical of the ol’ “It’s [great thing] meets [great thing]” construction, but when Felicity McLean’s debut novel The Van Apfel Girls Are Gone was described to us as “The Virgin Suicides meets Picnic at Hanging Rock,” well, sometimes you just have to respect the sales pitch.

This tasty slab of Australian Gothic tells the story of Tikka Mallory, a young woman who returns to her home in the Australian bush to discover the truth about the traumatic summer when her childhood friends vanished. Equal parts mystery and coming of age story, The Van Apfel Girls Are Gone is out now from Algonquin Books, and we’re pleased to offer up this excerpt.

FROM ‘THE VAN APFEL GIRLS ARE GONE’ We lost all three girls that summer. Let them slip away like the words of some half-remembered song, and when one came back, she wasn’t the one we were trying to recall to begin with. Spring slunk off too. Skulked away into the scrub and there, standing in its place, was a summer that scorched the air and burned our nostrils and sealed in the stink. Like the lids on our Tupperware lunchboxes. “Jade Heddingly says if it gets hot enough your shadow will spontaneously rust,” I reported. “It’s spontaneously combust!” my sister crowed. “Jade Heddingly is an idiot and so are you, and anyway your shadow can’t combust or rust or nothing. Your shadow is always there, dummy.” “Not in the dark.” Mum was right: you can’t see your shadow in the dark. She stood at the kitchen sink ripping the heads off bottlebrush stems. Flitch flitch flitch. She snapped the dead blooms off at the neck and dropped them into the sink, where their fine spiky hairs were the same ferrous red as the scabs we picked off our knees. It was the year the Cold War ended. The year they stopped making Atari 2600s forever. I was eleven and one-sixth, but it wasn’t enough. By then we’d learned shadows vanished in the dark “What else did Jade tell you?” Laura said. She waited until Mum went into the laundry before she asked the question, so that the two of us were left alone at the kitchen table where we were pretending to do our homework. “About shadows?” “About anything. Go on, what else did Jade say?” Jade Heddingly was fourteen, which meant she was old enough to wear braces on her teeth but not so old that she used those teeth and her tongue and the rest of her mean mouth to stop saying “arks” instead of “ask.” Jade kept saying it wrong long after the rest of us had left behind “hostibul” and “lellow” and all those other word jumbles we said when we were little kids. “Why didn’t you arks my opinion?” she would whine. As if that would ever make you change your mind. “What else did Jade say?” I echoed. “Yeah.” I leaned in before answering: “She told me that to hide a dead body you bury it six feet underground and then bury a dog three feet above that.” “Why?” “So that the police sniffer dogs will only dig as far as the dead dog, and they won’t find the body below.” “That’s gross!” my sister squealed. “Well, you asked.” “Is it true?” “I don’t know,” I admitted. “Did she say anything else? You know, anything about— you know.” “Nothing.” “You sure?” “Yeah, I’m sure,” I said defensively. “Jade doesn’t know anything about it,” I added. She didn’t know nothing about nothing. What we all knew—even as far back as that—was that the valley stank. Jeez, it reeked. It smelled like a sore. Like something bad had been dug out before the sky was stitched back over, low-slung and bruised and suffocating. They never did work out why. It wasn’t Ruth’s fault, but. That valley had smelled bad long before any of the Van Apfel girls ever went missing there. Even from our house high on the western rim, the stench would waft up the gully and smack us in the face on a hot dry day, and they were all hot dry days once the Cold War had ended. That summer was the hottest on record. Back in those days the valley had only been developed in pockets. It was dissected by a cutting where a skinny two-lane road wound down and around and across the river and then slithered up and out again, but the real excavation work had been done long ago by something much more primitive than us. The valley was deep and wide. Trees covered both walls. Spindly, stunted she-oaks spewed from the basin, swallowing the sunlight and smothering the tide with their needles. Higher up there were paperbarks, and tea trees with their camphorous lemon smell. Then hairpin banksias, river dogroses and gums of every kind—woollybutts, blackbutts, bloodwoods and Craven grey boxes, right up to the anemic angophoras that stood twisted and mangled all along the ridgeline. At school we called the valley the “bum crack.” We steered clear of the Pryders and the Callum boys and the rest of that handful of kids who lived in the shanty-style shacks in clumps along the valley. But the strangest thing about the place wasn’t the kids who lived there. It wasn’t the silence, or the way the sunlight sloped in late in the morning and slid out again as soon as it could in the afternoon. No, the awful part was the shape of the thing. Those terrible, fall-able cliffs. The valley wasn’t V-shaped like normal river valleys; instead the whole canyon was a hollowed-out U. It was almost as wide at the bottom as it was at the top, as if an enormous rock had been chiseled out but somehow we’d gone and lost that too. It was a fat gap. A void. Even now its geography is only worth mentioning because of what’s not there. I used to spend hours down there on my own. I’d go when I was bored—when my sister was at Hannah’s—and when the wind was blowing the right way for a change and the stink wasn’t so awful. I’d pick fuchsia heath flowers and suck the nectar out of their tiny pink throats and then I’d pretend they were poisonous and that I was going to die. Back then dying was nothing to be afraid of. At least, that’s what Hannah once said her dad said, and her dad was told it by God. But then Hannah’s dad had never actually died and so said: “What would your dad know?” What none of us knew—what we’ll never know—is what happened to Hannah and Cordie that December. We knew about Ruth because she came back, her lip curled in a whine like she’d lost her lunch money, not got lost in the bush all alone. (Or worse: not alone. What if she wasn’t alone?) When they found her she was poking out of a deep crack in one of the boulders by the river. She was stuffed right down, shoved into the fissure as if she’d been trying to jump in feet first but the gorge had choked on her at the last minute. Had tried to spit her back out. Wade Nevrakis told us that when the police found her there were so many flies crawling over the surface of Ruth’s rock that it looked like it was spinning. But Wade Nevrakis’s parents ran the deli near our school so I don’t know why Wade thought we’d believe his parents were anywhere near it. (But when Kelly Ashwood spread it that Ruth was alive enough to say: “C’niva Rainbow Paddle Pop if I say my throat hurts?” well then, you could almost believe it because everyone knew Kelly Ashwood was a tattletale, and also that Ruth was a pig.) It took thirteen detectives, two special analysts from the city, forensics, plus all the local area command and the SES— State Emergency Service—volunteers to find Ruth in the rock that day. Them and the black cockatoos that circled in the sky above. They shouldn’t have been there, those cockatoos. Not in numbers like that and not during breeding time, and yet there they were, going around and around, over and over, like a record getting stuck on a scratch. When they discovered Ruth her eyes were squeezed shut as if she’d seen enough. Like she couldn’t bear to look. And except for a smear of dirt running the length of her left cheek and a few dead pine needles sticking out of her plait, she appeared untouched, and as though she was praying. Her parents would’ve liked that. We all heard the wail of the siren that day as it wound jerkily up the bends and out of the valley, which by that stage of the early afternoon was already creeping with shadows. The noise of the siren rose and fell with each turn. Louder then fainter as the drivers negotiated each bend. Mrs. Van Apfel was at the police command post at the time, waiting for Detective Senior Constable Mundy, and they say she froze when she heard the siren because the news about Ruth hadn’t reached them yet. Mrs. McCausley, who lived on the corner of our cul-de-sac, was at the command post making tea for the searchers. She said Mrs. Van Apfel swung her head towards the sound, like a dog that heard its owner’s whistle. Each rise and fall of that siren’s song, Mrs. McCausley told us, “was as if God himself was opening and closing the door on that poor woman’s pain.” Mrs. McCausley had been “Tuppered.” Least, that’s what she told me. “She’s been what?” Mum said when I reported it back to her. “There’s no such word.” Mum was a librarian so she knew all about words. Words and overdue notices. “Is,” I insisted. “Mrs. McCausley told it to me.” But it took several back-and-forths to work out what she’d meant, and it wasn’t until I explained how Mrs. McCausley’s life had changed for the better when she’d learned Tupperware products were guaranteed against chipping, cracking, breaking or peeling for the whole lifetime of the product that Mum really understood where she was coming from. “Bloody Tuppered,” I heard her say to Dad that night as I hung over the bannister eavesdropping on their conversation. “Selling Tupperware to our kids now.” And she sounded cranky, and so did Dad, even though I hadn’t bought anything. Mrs. McCausley sold Tupperware, though it was more a hobby than a job. “Just enough to keep me out of trouble,” she said. Though anyone could see Mrs. McCausley’s door-to-door Tupperware visits were more about unearthing strife than trying to stay out of its way.

Excerpted from “The Van Apfel Girls Are Gone” by Felicity McLean, out now from Algonquin Books. All rights reserved.