When novelist Elena Ferrante embarked on a year of writing weekly columns for The Guardian, she saw it as a writing challenge - to work as, in her words, "an author of novels, taking on matters that are important to me and that—if I have the will and the time—I’d like to develop within real narrative mechanisms."

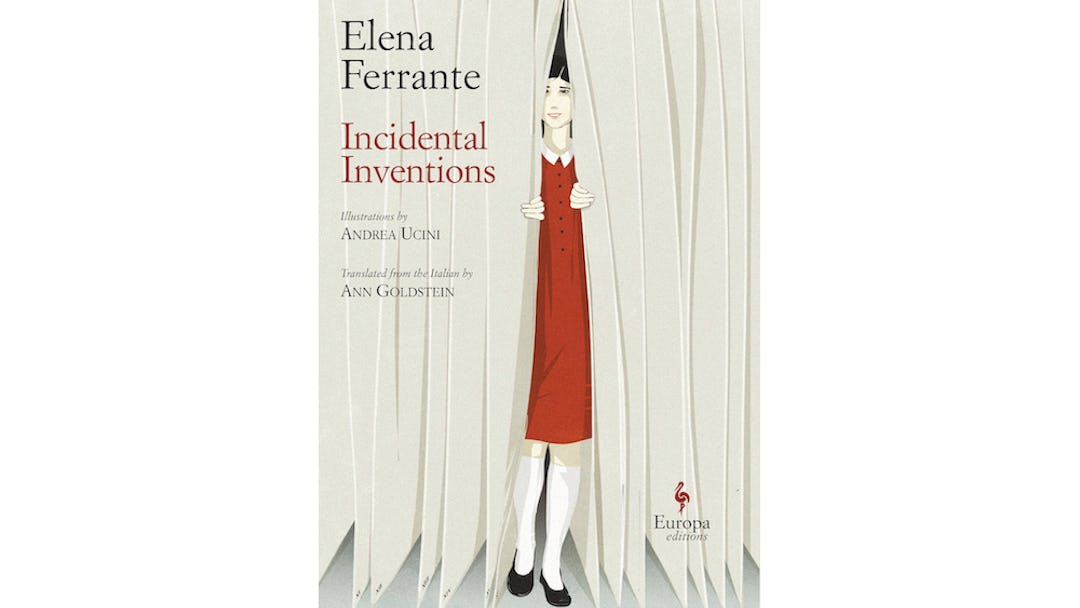

Those columns, ranging a wide variety of topics suggested by her Guardian editors, are collected in the new volume Incidental Inventions, translated by Ann Goldstein (the acclaimed translator of Ferrante’s novels) and accompanied by Andrea Ucini’s illustrations. We're honored to present this excerpt.

"MOTHERS" (25 August 2018):

My mother was very beautiful and very clever, like all mammas, so I loved her and hated her. I began to hate her when I was around ten, maybe because I loved her so much that the idea of losing her threw me into a permanent state of anxiety, and to calm myself I had to belittle her.

Sometimes she seemed to me to be beautiful and clever just so that everyone would see me as ugly and stupid. I couldn’t think any thought of my own; I had only her thoughts in my mind. I felt oppressed, tormented by her mania for order, by her outmoded tastes that suffocated mine, by her idea of just and unjust. For a long time, I felt that to stop loving her was the only way I had to love myself— even to have a myself to love.

A secret cord that can’t be cut binds us to the bodies of our mothers: there is no way to detach ourselves, or at least I’ve never managed to. It’s impossible to go back inside her; it’s hard to move past her shadow.

So I quickly put many other bodies between hers and mine—bodies with which I could be the boss, quarrel, make love, appear wise or foolish—constructing a world alien to hers. I wanted her to feel uneasy if she merely looked in on it: that happened often, and she escaped in silence.

Over the years, she withdrew. She got smaller, she lost beauty and cleverness, she stopped asserting her own superiority in everything, her words no longer had weight.

For a while I felt free. Then people began to say things like, “You laugh like your mother, you’re stubborn like your mother, you have your mother’s hands.” One morning I looked at myself in the mirror and I recognised her: she was there, in my body. And to my surprise it began to bother me less and less; slowly I discovered her in my gestures, in a particular way of showing or controlling feelings, in my voice. If it was impossible to go back inside my mother, it was very possible that she had been inside me since birth, and that she could be found inside me even when I fought to escape her—even when I thought I was free of her.

Ever since I realised that finding myself meant finding her, and accepting and loving her the way I did as a child, I have felt soothed. Sometimes reconciliation is taken to be the capacity to forget the wrongs we’ve suffered. And maybe it’s true, but not in our relations with our mothers. I was reconciled with mine when I felt those wrongs—what seemed to me wrongs—as part of myself, essential for my development. So essential that they now appear an invention of mine, a brightly coloured exaggeration.

From "Incidental Inventions," out now from Europa Editions. All rights reserved.