Few movie buffs would argue that Sidney Lumet – whose output included such classics as 12 Angry Men, Serpico, Dog Day Afternoon, Network, and The Verdict – was one of the finest filmmakers of the 1970s (one of the most important eras in the medium’s history). Yet he’s rarely discussed in the same rarified air as contemporaries like Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, and Frances Ford Coppola; perhaps it’s because he’s no longer with us (he died in 2011), or because his journeyman craftsmanship didn’t leave quite so pronounced an authorial stamp on his work. But there’s no denying the power of a Sidney Lumet picture: grounded, authentic, character-driven, and intelligent.

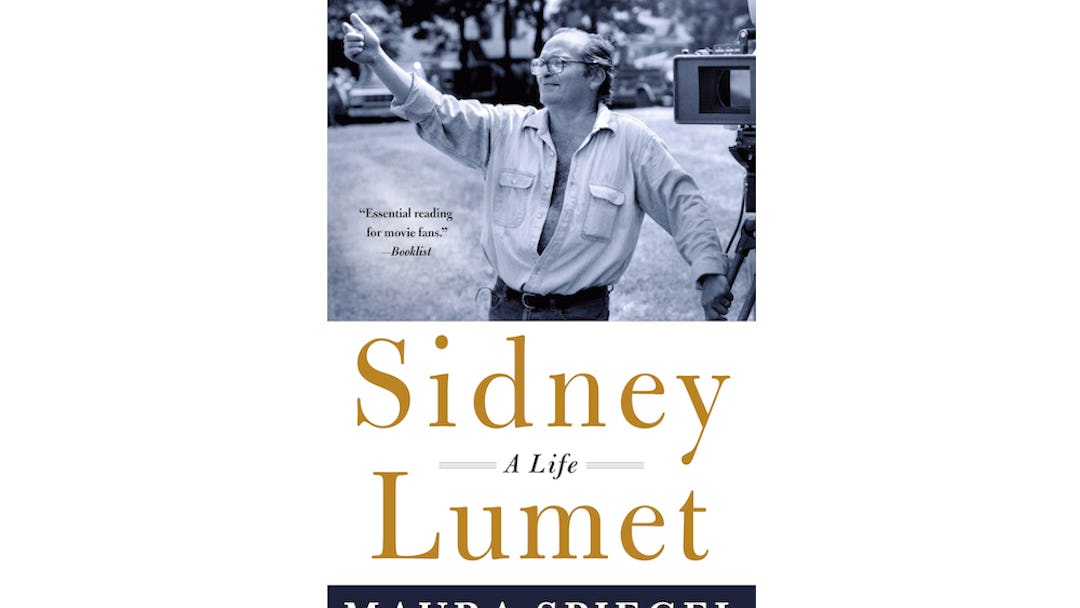

Columbia University film and literature professor Maura Spiegel will hopefully adjust the conversation to a proper appreciation of his gifts with her new book Sidney Lumet: A Life (out this week from St. Martin’s Publishing Group), the first and likely definitive biography of the late filmmaker. In this excerpt, she walks the reader through the making of one of his finest films: the 1975 Al Pacino vehicle Dog Day Afternoon.

FROM "SIDNEY LUMET: A LIFE":

“What you are about to see is true—It happened in Brooklyn, New York on August 22, 1972.”

-Opening, Dog Day Afternoon

“The day in question was Tuesday, August 22, 1972. The temperature was 97 degrees. I was driving out to Long Island on the expressway, and, as was my custom, I was listening lethargically to the endless repetitious news bullets on WINS. . . . Then suddenly there was real news of the most ridiculous kind. A bank was being held up in Brooklyn. The police had arrived. Hostages were being held. A state of siege was in force. Demands were being made. It was a familiar scenario, but with bizarre variations. One of the bank robbers demanded that his wife be brought to him, and, when the police complied, it turned out that the ‘wife’ was a transvestite. I began to suspect that Andy Warhol and Paul Morrissey had staged the whole operation as a tasteless parody of the terrorism around us.”

-Andrew Sarris, Village Voice, September 29, 1975

The day before shooting began on Dog Day Afternoon Pacino got cold feet. As Sidney told it, “He asked me and the screenwriter, Frank Pierson, to come up to his house for some cockamamie reason.” When they got there, Pacino was “crawling around on all fours, barking like a dog.” Sidney’s sensitive query: “Al, what the fuck is this?” Pacino responded that he was “out of control” and that he couldn’t do the film. Pacino was panicked because his career had just taken off and he feared that this role would end it; up to that point no major Hollywood star had played a gay man. Sidney’s strategy was not to try to calm Pacino down, but instead to relate Pacino’s current state of mind to the character of Sonny, “what the character must have felt when he decided to rob the bank.” Sidney was confident that “the actor part of him would be digesting all these feelings and saying, ‘Hey, I can use that in the performance.’” Pacino showed up the next day right on time.

Pacino was in, but he required changes to the script regarding the relationship between Sonny and Leon, his transitioning wife. Footage of their wedding was cut, and a farewell kiss outside the bank was traded for the incredible farewell phone call between the two. Sidney too had worried about audience reaction to that kiss. The balcony reactions at the Loew’s Pitkin in Brooklyn when he was a teenager were alive in his memory, the rowdy boys hooting and booing Leslie Howard, who appeared too effeminate for their taste. He didn’t want anything to push those buttons.

Prior to shooting, Sidney had consulted with the Gay Activists Alliance and gotten a thumbs up. For the filming, Sidney called upon members of the Gay Liberation Movement to be the extras in the crowd, including a teenaged Harvey Fierstein, whom Sidney would later cast in Garbo Talks. The movie was warmly received in the gay press.

Casting Leon, mainstream American movies’ first openly transsexual character, took some time. As Burtt Harris recalled the auditions, “We had every performer, every drag queen performer in New York, and all they ever did was Geraldine Page in Summer and Smoke. They almost were identical, until we got Chris Sarandon. His approach was: ‘All I gotta do is be in love with this guy, want to marry him and get a sex change operation. Simple.’” And that fit with Sidney’s idea to treat what could be seen as outrageous in a matter-of-fact manner, relatable. Not to milk it. His famous one-line direction to Sarandon: “A little less Blanche DuBois. A little more Queens housewife.”

Sidney’s characteristic consideration for the people who lived in the vicinity of his location-shooting—including requiring silence of the crew when shooting at night and making sure the lights never got pointed at apartment windows—was ratcheted up since they would be on one Brooklyn block in Prospect Park West for weeks with a massive cast, sirens, and a helicopter overhead. He offered neighbors the option of a paid hotel stay or they were welcome to watch the shooting; heads out of windows would not be out of place.

And unique to this film was Sidney’s use of improvisation. Sidney’s enormous respect for writers had been one of the reasons he had steered away from this process in the past. This time Sidney had the actors improvise dialogue that he recorded and that he and screenwriter Frank Pierson would cull, shape, and give back to the actors. Pacino recalled the process:

With Sidney, he would say, “Okay, we’ve got this scene, we haven’t quite gotten it. Let’s go work on this thing.” Right there, right on the set. And he has me and the actor improvise. . . . Mainly we were able to do it, because we had been working on it for weeks, maybe months, so we know the people we’re playing a little bit. We did three improvisations that he taped of the scene. He takes all the data on that, and he translates it and writes one scene from the three improvisations. You know, you don’t do that with the whole script, but at that particular moment, it was a 15-minute scene, that’s what he did. These are the kinds of things that come up . . . and sometimes you get gold.

Some of the most iconic lines in the film were improvised on camera, including Sonny’s galvanizing “Attica, Attica,” which beloved A.D. Burtt Harris had whispered to Pacino just before the camera rolled. When Sal (John Cazale) answers Sonny’s (Pacino) query about what country he’d like to go to with “Wyoming,” Sidney had to slap his hand over his mouth to silence his laughter so as not to ruin the shot. This was a thrillingly organic process, just exactly right for this great film that earned Sidney his second best directing Oscar nomination, along with nominations for best film, best actor, best actor in a supporting role for Sarandon, and best editing. Frank Pierson won for best original screenplay.

When Sidney was asked about what Pacino had needed to achieve this astonishing performance, Sidney replied with characteristic forthrightness, “The creation of the character is really Al’s own. He understood something about that man that is irreplaceable, and I don’t think a director can ever give—he understood him down to his bone marrow.”

From "Sidney Lumet: A Life" by Maura Spiegel. Copyright © 2019 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group.