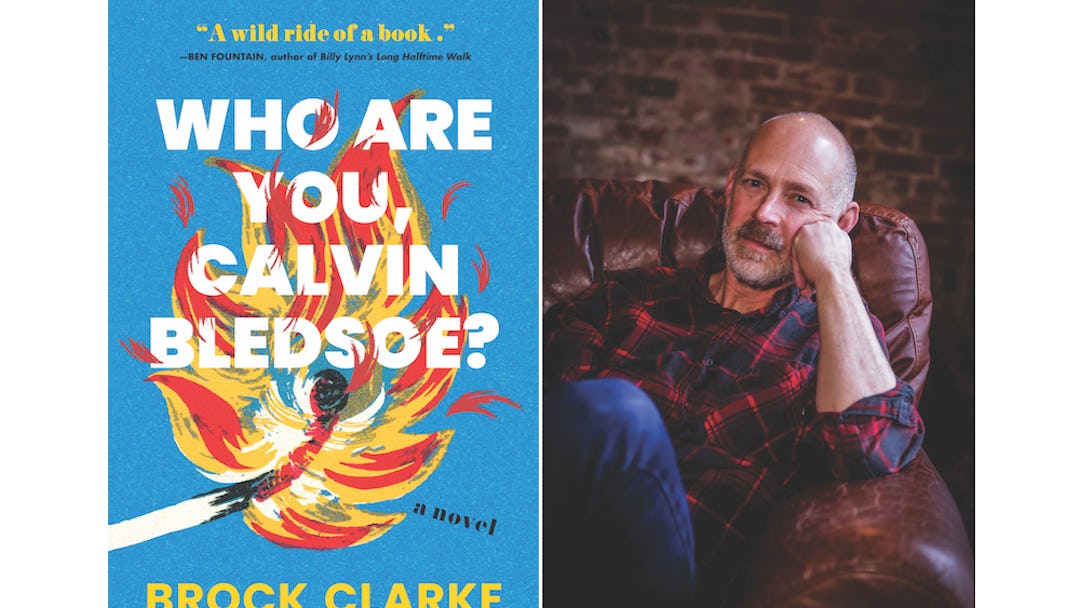

In his new novel Who Are You, Calvin Bledsoe? (out now from Algonquin Books), author Brock Clarke tells the story of Calvin Bledsoe, a recently divorced blogger for the pellet stove industry who finds himself untethered, for the first time in his life, after the deaths of his parents. But when his eccentric aunt appears shortly thereafter, and insists he accompany her on a trip to Europe, he finds himself asking who he is - and where he's going.

We're pleased to present this excerpt from the opening chapter of this funny, thoughtful work.

FROM "WHO ARE YOU, CALVIN BLEDSOE?":

1.

My mother, Nola Bledsoe, was a minister, and she named me Calvin after her favorite theologian, John Calvin. She was very serious about John Calvin, had written a famous book about him—his enduring relevance, his misunderstood legacy. My mother was highly thought of by a lot of people who thought a lot about John Calvin.

2.

My father, on the other hand, was a high school coach—football in the fall, basketball in the winter, baseball in the spring. In the summer he ran clinics for athletes who would be playing their respective sports during the regular school year. His name was Roger Bledsoe. My father has left this life, and he is also about to leave this story, so before he does, let me tell you a few things about him. He was seventy-seven years old when he died. He was bald on top and was always neatly dressed: pressed chinos, tucked-in oxford shirts—even his boat shoes were polished. His eyebrows were the only unkempt things about him: they curled and hung over his eyes likeawnings.

So I remember what he looked like. I also remember his sayings. “You bet your sweet bippie,” he liked to say, and also, when he needed to go to the bathroom, “I’m going out for a short beer.” But mostly he liked to say, “This isn’t my first rodeo, you know.” Most of his pregame pep talks included that phrase. Most of his conversations did also. Several months before he died, I told my father that my wife and I were separating. This was after one of my father’s baseball games. I was forty-seven years old, and I still went to all my father’s games, went to all my mother’s services, too. I have no memory of whether his team had won or lost that particular game, but I do remember that the wind was up, that my father’s eyebrows were waving at me like cilia. “So, you’re getting a divorce,” he said.

I insisted that wasn’t necessarily so. “Lots of people who get separated don’t end up getting divorced,” I said, and he squinted at me skeptically and said, “This isn’t my first rodeo, you know.”

3.

And then he died of a heart attack. Three days later my mother and I were in the cemetery, standing over his grave, next to the pile of dirt. The rest of the mourners had left. The hole was still open. The cemetery workers were waiting there with their shovels, their backhoe idling and rattling loudly behind them. Thiswas in Maine. It was November. The air was filled with snow and with the feeling of last things. I wondered if the workers sensed this, too. This was probably the last hole they would be able to dig before the ground froze.

“That was a beautiful eulogy,” I told my mother. In truth, the eulogy had surprised me. I’d expected it to be more, I don’t know, personal. I’d heard her give nearly identical ones at the funerals of friends, members of her church, even relative strangers. Those eulogies, like my father’s, had been filled with inspiring lessons about this life and the next as taught to us by the theologian . . . well, you know which one. It was strange: my mother and her book and her sermons always insisted that while Calvinists were reputed to be severe and full of judgment, John Calvin himself had been forgiving and full of love. But she always wrote and said this in a way that seemed severe and full of judgment.

“You must have always wondered why your father and I stayed together for as long as we did,” my mother said—to me, I guessed, although she was looking at the hole. This surprised me even more than the eulogy. In fact, I had not wondered this at all. I had not ever even considered my parents’ not staying together a possibility. I had not ever even considered my wife and me not staying together a possibility either until it actually happened. But I didn’t say this to my mother. I wanted there to be peace between the living and the dead and also between the living and the living. “Why does anyone stay together for as long as they do?” I asked—rhetorically, I thought, although my mother answered anyway.

“God,” she said, “family, fear, loyalty, sex, security, compas- sion, companionship, complacency, children, guilt, money, real estate, health insurance, not wanting to eat alone, not wanting to go on vacation alone, not wanting to watch television alone, not wanting to drink alone, not wanting to go on cruises alone, not wanting to go on cruises at all, not wanting to leave one person and find another person who then wants to go on cruises, not wanting to leave a person and not find another person at all, not wanting to find another person, not knowing what you want, not knowing what your problem is, love.”

I had never heard my mother say anything remotely like this—it definitely didn’t seem like a lesson she could have learned from John Calvin—but before I could say that, or anything else, my mother nodded in the direction of the cemetery workers, and they advanced on my father’s grave with their shovels and their backhoe, and a few minutes later he was truly buried, and only then did it feel like he was truly gone.

4.

If you live, as I did then, in a small town in central Maine, there is no more visible a job than that of a high school coach or a minister. Is it any surprise that I chose a somewhat less visible job? I became a blogger for the pellet stove industry. You may not know that there is a pellet stove industry, or that it is has a blogger, but there is, and in fact it has two. I am the blogger who extols the virtues of the pellet stove: its cost and energy efficiency; the way it’s good for the environment and the economy; the way it sits on the crest of the wave of the home-heating future. The other blogger is named Dawn, and Dawn’s job is to spew vitriol at the makers and the sellers of the “conventional woodstove.” This is what she calls it in her blog, always in scare quotes: the “conventional woodstove.” All Dawn’s Monday blog posts begin with a story of someone she’s met at a “weekend party” who has asked her what’s so wrong with the “conventional woodstove.” If you’re ever at a “weekend party” with Dawn, please don’t ask her what’s so wrong with the “conventional woodstove.” Because she will say, “Oh, don’t get me started.” And if Dawn says that, it means she’s already gotten started.

5.

Anyway, not six months later, my mother died, too, at the age of seventy-nine. Her car had apparently gotten stuck, or stalled, on the railroad tracks just outside of town and was hit by a north-bound train carrying propane tanks destined for Quebec. The train struck the car directly in its gas tank. Which exploded. As did the propane tanks. The propane-and-gasoline-fueled fire was so intense that even my mother’s bones, even her teeth, had been burned into nothing. There was nothing left of her at all. The volunteer firemen said they’d never seen anything like it.